That's What's Up: R-Rated Movies That Inspired Saturday Morning Cartoons

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What was the deal in the '80s where they made Saturday morning cartoons out of grown-up movies like RoboCop and Toxic Avenger? — @BrosOfLostNerds

Back when I was working at the comic book store, there were few things that would blow my mind as delightfully as when we'd get a new collection of toys that would have something from RoboCop and the Ultra Police, a line where Murphy's partner Anne Lewis was represented as a S.W.A.T. team specialist armed with a crossbow. It's that weird kind of fascinating where you see something that by all rights should not exist and just have to know how it came about. And as it turns out, it all starts with Ronald Reagan.

No, really. That's not a jokey lead-in to the rest of the column. This one actually starts with Ronald Reagan.

Morning in America for G.I. Joe

When Reagan was running for President in 1980, a big part of his platform was the removal of regulations imposed on businesses by the federal government, and—for our purposes today, at least—there was one area where he was extremely effective. After he was elected, he was quick to appoint Mark S. Fowler, also a pretty big fan of deregulation, as commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission in May of 1981.

Before long, the FCC's rules about limiting advertising in broadcasts were eliminated, and the landscape of television was changed forever. This is, for instance, why infomercials suddenly became a big thing in the early '80s, because television stations were now allowed to sell full half-hour blocks to businesses so Ron Popeil could extoll the virtues of the Veg-O-Matic, uninterrupted by any of that pesky entertainment. They'd even resist pressure to reverse that decision throughout the decade, until it was pretty much normalized as just part of kids' TV.

The biggest change, however, came for children's television, something that brought Reagan and Fowler's FCC into conflict with a group called Action for Children's Television, which had lobbied for changes in children's TV since it was formed in 1968. Their usual target was excessive violence in programming directed at kids—they were the reason that Space Ghost and The Herculoids were taken off the air and replaced with relatively nonviolent shows like Scooby Doo, for instance—but they were also pretty concerned with the idea of marketing toys to impressionable children who weren't able to tell the difference between a TV show and the ads that accompanied it. And they weren't the only ones, either. In 1969, when Mattel launched a cartoon based around their Hot Wheels line, the FCC received complaints from other toy companies, alleging that having a show built around a toy line was giving Mattel an unfair advantage in the marketplace.

When Fowler and Reagan swept in, though, those restrictions were eliminated, and by 1983, toy companies were taking over the airwaves with shows based on their brand new lines of action figures.

Fighting for freedom and selling you toys

Mattel jumped on with He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, and Hasbro quickly followed with G.I. Joe, Transformers, Jem and the Holograms, and My Little Pony, among others, and the formula worked. Those toy lines wound up being hugely successful, largely because they went hand in hand with toys that showed kids how exciting those toys could be.

And nobody was really surprised by that, either. In the late '70s and '80s, Kenner made a mint off Star Wars figures, precisely because they were making toys based on a story that kids already liked. With the toy cartoons that swept in after the FCC deregulated children's programming, the toy companies were able to reverse that formula: make the toys first, and then use them to create the stories that kids liked.

Even when the shows were good—and as a huge fan, I'd argue that Jem and G.I. Joe hold up incredibly well for what were nominally toy commercials for babies that hit the airwaves 30 years ago—the toy sales were driving the franchise every step of the way. You can see it in the comics, too. Larry Hama, the creator and primary writer of G.I. Joe for its entire run at Marvel, once said in an interview that he only ever plotted ahead "about two or three pages at most." That's hard to imagine given how intricate and connected the plots of that book feel when you take it as a whole, but I have to imagine that at least part of it was because you never knew when Hasbro was going to call up and tell you to include the latest action figures as new recruits for G.I. Joe and Cobra.

That's one of the reasons that the new wave of cartoons that came in the early '90s, like Batman: The Animated Series, felt like such a big deal. There was definitely an accompanying toy line (and a whole money-making machine that encompassed movies and comics), but it felt like the first show for kids in a while that was actually driven first and foremost by story, rather than by getting you excited about Neon Talking Super Street-Luge Batman.

A joke created at a kitchen table becomes the most popular thing in the world

But the thing about shows like G.I. Joe and Jem is that a creator like Larry Hama or Christy Marx only comes along every so often to hand you a premise that's both toyetic enough for a line of action figures and good enough to keep children watching for the whole half hour. So while cartoons based entirely on toy lines never went away, producers and toy companies were very quick to realize they could skip out on at least a little bit of the hard work by taking existing properties and building everything around them instead of creating them from whole cloth.

Unsurprisingly, one of the first big examples of this was DC Comics. Super Friends had been around in one form or another since 1973—and Batman and Superman were pop culture powerhouses for a couple decades before that, even—but it wasn't until 1984 that the show was retooled as The Legendary Super-Powers Show, with a whole line of action figures, vehicles, and playsets released along with it, a direct result of the deregulation. And that, incidentally, was what allowed Jack Kirby to get some royalties for characters like Darkseid that he'd created at DC, when Jeanette Kahn and Paul Levitz arranged for him to redesign the characters for the toy line.

The all-time heavyweight champion of all this toy licensing was, of course, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. What had started as a parody of the most popular trends at Marvel Comics in the mid-'80s (X-Men's teenage mutants and Daredevil's ninjas, the Hand) had quickly ridden the black-and-white publishing boom of the mid-'80s to become a fairly adult-oriented comic series. In 1987, though, it was relaunched as a cartoon for kids with an accompanying toy line that quickly became the most popular thing in the world, and along with the Star Trek license, kept Playmates Toys as a going concern for the next couple decades.

But it's not just about the toys. There was something else that happened in the '80s that was a pretty big factor in making Saturday Morning a lot more weird: cable TV and the rise of the video store.

Part man. Part machine. All toyetic.

It might seem hard to believe for younger readers—and as someone who spent about a third of his childhood staring at VHS box art, I find it pretty strange too—but there was a time when if you wanted to watch a movie, you pretty much had to go to a movie theater. There was a chance you could catch something on TV during that weekend afternoon timeslot if your local affiliate had picked up the rights, but second-run theaters were a pretty huge thing, and even mainline movie theaters would keep stuff like Star Wars in circulation for years because they were guaranteed to draw an audience.

In the '80s, though, the popularization of cable TV and home video changed the game completely—maybe even more than the introduction of streaming services in the 21st century. With a channel like HBO, viewers had access to movies pretty much constantly, and while you were still at the mercy of their schedule, a video store meant that if you had a VCR, you could watch whatever, whenever. With a video store, you didn't even have to shell out the money to own it. A couple bucks, and you had access to a massive library that, in the beginning at least, was so desperate for content that stores were willing to line their shelves with whatever they could get their hands on, whether they were major blockbusters or low-budget releases made on the cheap. Like, say, The Toxic Avenger. More on that in a second.

The practical effect of all this was that while theaters would make a token effort to keep minors out of R-rated movies, having access to all that stuff in your own home removed that gate and gave a level of privacy that would allow kids to watch anything, assuming they either had permissive parents or were good at being sneaky about it.

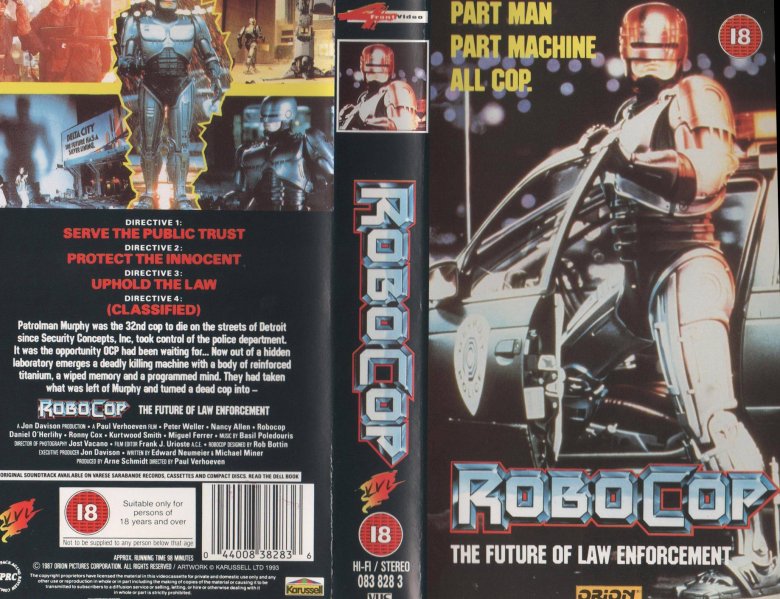

For a kid in the '80s, seeing an R-rated movie became a very achievable status symbol, something that was forbidden enough to be seen as cool, but not difficult enough that you couldn't pull it off pretty easily, especially if your parents weren't paying complete attention. I mean, if you haven't actually seen RoboCop, the VHS tape looks like it could be perfectly appropriate for kids. They didn't exactly put Bob Morton doing lines of cocaine with sex workers on the back of the box, you know?

And if we're being honest, it's not always about sneaking one past your mom. Kids tend to like action-adventure stories with loud noises and cool-looking characters, and seemingly "adult" movies like RoboCop, Terminator, and the later Rambo sequels all had that going for them. So as the grindhouse theater gave way to late-night cable and the video store, kids started to understandably gravitate to characters that were never intended for their demographic. RoboCop the movie might be a hyperviolent satire of consumerism made for adults, but RoboCop the dude looks like a toy.

The RoboCartoon

There were a few understandable approaches to do something similar to the movies that would be a little more kid-friendly from the start of things. C.O.P.S., aka C.O.P.S. 'n' C.R.O.O.K.S., for example, was basically a G.I. Joe knockoff with a team of sci-fi police officers led by a dude named "Bulletproof" Vess who was basically just a kids' cartoon version of RoboCop, right down to an origin story that included him being mortally wounded and rebuilt as a cyborg.

But there's another line of thinking, too, and it basically amounts to asking why you'd go through all the trouble of creating a middleman when you could just go ahead and get the license for the thing that already had name recognition, and that the kids who were staying up to sneak a look at late-night HBO were already aware of. If you did that, then you not only got the benefits of building off an established property, you gave the kids who already liked RoboCop (to stay with that example) an easy excuse to buy your toys that wouldn't bring parents' groups down on you for marketing a blood-soaked, foul-mouthed action movie to kids. You just make a version with the edges filed down, adhering to the strict Broadcast Standards and Practices rules about never showing blood or using the word "kill," and base the toys on that instead. Why not?

Well, the answer to "why not" is actually pretty obvious: because it's friggin' insane. Look at that RoboCop cartoon intro! Even if they're skipping over the blood, that thing literally has the scene where Clarence Bodicker and his boys blow Alex Murphy's hand off with shotguns! That is wild!

Rambo: The Force of Freedom

But it was an idea that took hold in the weirdest possible ways, and while it's one of the most fun to talk about, what with being based on a movie where a guy gets his ding-dang shot off, RoboCop wasn't the only one.

I think the all-time weirdest has to be Rambo: The Force of Freedom, which hit airwaves for a 65-episode run in 1986. As cartoonish as those movies might've eventually gotten, keep in mind that at the time, the only ones that were out were First Blood and Rambo: First Blood Part II—a tense thriller about a veteran dealing with PTSD and a country that no longer wants him, and a hard-R action movie with 75 on-screen kills, respectively. They made that into a cartoon for kids, and included an almost Sailor Moon-esque transformation sequence for every time Rambo powered up by putting on his headband. There's even a Christmas episode!

And as completely buck wild as that is, it's kind of easy to see why they'd do it. It had the name recognition, it was a pop cultural touchstone that was being parodied everywhere, lodging it firmly into the zeitgeist, and, maybe most importantly, Rambo used a knife. I once interviewed the producers of Batman: The Brave and the Bold, and when I asked how they came up with the idea of giving Batman a laser sword hidden in his utility belt, part of their answer was that toy companies love swords, because swords sell. Presumably, knives work the same way—although not that well, considering that those 65 episodes amounted to a three-month run that found Rambo off the air by December.

Toxic Crusaders, the cartoon based on Troma's Toxic Avenger films, took a similar route, but it also had the benefit of being an easy high concept video store customers were familiar with that also hit right when environmentalism was becoming a prominent social movement—it's not really a coincidence that it hit TV right around the same time as Captain Planet.

It's worth noting that in his memoir, All I Need To Know About Filmmaking I Learned From the Toxic Avenger, Troma's founder and primary creative force Lloyd Kaufman gave a lot of credit to costume designer Susan Douglas, saying that her design for Toxie was a lot friendlier than his original idea of a super-gross, misshapen mutant. He even goes on to talk about how they tried to re-create that success by creating a more kid-friendly character in Sgt. Kabukiman: NYPD, but that he couldn't rein in his gross-out sensibilities enough to create something that would catch on with a younger market, and ended up with something that alienated both the kids he was trying to appeal to and Troma's hardcore cult-movie audience.

Point being, that's how weird kids' cartoons were getting in the late '80s and early '90s. They not only made one about the Toxic Avenger, they thought they could get another one made about Sgt. Kabukiman.

Conan: The Adventurer

The only one of that roster that even kind of makes sense is 1992's Conan the Adventurer, but keep in mind that the emphasis there is on kind of.

I mean, on one hand, Conan had been a fixture in Marvel Comics for decades at that point, and while the 1982 movie was rated R, it's hardly the murderfest that you'd get from Rambo. Even the follow-up, Conan the Destroyer, dropped down to PG, and if you look at those VHS boxes, they're basically functionally indistinguishable from He-Man.But here's the problem. Even in the comics, Conan basically does two things: He has sex, and he kills people. And the way that the cartoon dealt with all that is so blunt and toothless that it's hilarious.

Meet Needle, he's the worst

Conan's family wasn't killed, they were turned to stone, and while he definitely has a sword to swing around, he never actually hits the bad guys with it. He just waves it around near them so that the magic can send them back to another dimension. And just in case that wasn't enough, my dude has a talking baby phoenix sidekick named Needle who lives in his shield, and may be the worst cutesy sidekick in cartoon history. Yes, worse than Snarf.

That said, Conan the Adventurer was one of the shows that marked the end of the glut of weirdly toy-driven cartoons based on highly inappropriate source material. Part of it was that there were enough failures to show that it wasn't a reliable formula—RoboCop, Rambo, and Conan didn't last long at all—but I think you can chalk it up to changing sensibilities, too. Batman showed more sophisticated storytelling could work, and while there were definitely massive toy lines for X-Men and Spider-Man, their reliance on comics to provide storylines meant that they never seemed all that toy-driven either. By the time Cartoon Network got going as a major concern, toys based on the shows became a secondary concern to other toys you could sell if you made the shows good enough to keep everyone's attention.

And sadly, all that happened before we could get a Die Hard cartoon where John McClane was joined by his cowardly pet piece of glass, Shardy. I mean, honestly, is that any weirder than TaleSpin?

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."