The Untold Truth Of John Carpenter's Halloween

In the fall of 1978, a terrifying phenomenon crept across America. Young people would go out for an innocent night at the movies, only to return home screaming to all of their friends about how a film director most of them had never heard of had scared the bloody hell out of them. Like in every scary movie you've ever seen, these friends would invariably have to check out the alleged horror for themselves... only to suffer the same grim fate.

The man behind the phenomenon was a young filmmaker named John Carpenter, and his instrument of terror was a low-budget B movie that producers were only hoping would make back its meager budget. Instead, it gave birth to the cash cow that is the modern slasher film, establishing virtually every one of that genre's tropes and dramatically announcing its director as a major new talent. Here are a few things you may not have known about one of the greatest and most influential horror films of all time—John Carpenter's Halloween.

It was an independent feature

Halloween is one of only a few horror films to be selected for the National Film Registry. But it wasn't exactly a major production—the film was the brainchild of producer Irwin Yablans, the founder and chief executive of Compass International Pictures, a small independent production company with exactly zero features under its belt. Yablans, looking for a director for his first feature, happened to catch Carpenter's second film—Assault on Precinct 13, a 1976 actioner that looked great and had been shot on a very modest budget.

A graduate of USC film school, Carpenter had previously developed a school project into his 1974 debut Dark Star before landing the director's job on Precinct 13, an ultra-low budget indie that failed to drum up much interest in the States but received a rapturous critical reception in Europe. With his strong visual style and ability to innovate on a tight budget already evident, Yablans hired Carpenter to helm Compass' debut picture—although at the time, Yablans only had the seed of an idea for his film. Carpenter and his partner Debra Hill would write the script, and financier Moustapha Akkad put up the $320,000 budget.

It wasn't Carpenter's idea

Yablans' idea was simple enough: a psychopathic killer stalking babysitters. In fact, early in pre-production, the project had the working title The Babysitter Murders. Speaking with Entertainment Weekly, Carpenter remembered, "I was finishing [directing] a TV movie called Someone's Watching Me! when Irwin Yablans called and said, 'Why don't we set it on Halloween night—in fact, why don't we call it Halloween?' I have to give him credit. So Debra and I... began writing."

Carpenter and Hill filled in details by reaching back into their childhoods; the small town where the film takes place was named Haddonfield after the town in New Jersey where Hill grew up, and many of the street names were ported over from Bowling Green, Kentucky, where Carpenter was raised. Carpenter came up with the urban legend-like notion of the small town with a dark secret that's revisited by the horror of its past on Halloween night, and then, as Hill explained to Fangoria, "We wrote the whole thing in three weeks. Then we just had to find the right actors."

Jamie Lee Curtis wasn't the first choice

Especially important was casting the part of Laurie Strode, the movie's heroine. Tommy Lee Wallace, Carpenter's friend and one of the film's editors, explained, "This was a time that women were asserting their rights like never before, and Debra was a very assertive woman. No way she was going to have a weeping violet type as her heroine." Carpenter was keen to cast Annie Lockhart, the daughter of Lassie actress June Lockhart—but Hill had other ideas.

19-year-old Jamie Lee Curtis was a television actress at the time, having an ongoing role in the series Operation Petticoat. Carpenter, who didn't watch television, had never seen her work—but Hill was convinced she'd be perfect for the role. "Jamie is very much like Laurie," Hill explained. "She's very introspective, very complicated. There are many interesting facets to Jamie, and there's a very beautiful innocence that the business still hasn't ruined." One small detail was all it took to convince Carpenter—Curtis also happened to be the daughter of Janet Leigh, perhaps the original scream queen, whose shower had been rudely interrupted by Norman Bates in the 1960 classic Psycho. Carpenter basically saw this as free promotion, and Curtis was given the part.

Carpenter pulled out all the tricks

If the film doesn't look particularly low-budget, it's because Carpenter was a master at making something from nothing. As there was no room in the budget for a costume department, the entire cast's wardrobe was purchased on the cheap at local department stores; Curtis' cost less than $100. Michael Myers' mask was crafted from a repurposed William Shatner mask, painted white and with a few other minor adjustments—Wallace (who, in addition to being co-editor, was also the production designer, art director and location scout) bought it from a local costume shop for $1.98.

Many other ways were found to keep production costs low. Cinematographer Dean Cundey offered up his own Winnebago for the crew; the house featured in the film as the Myers' home was abandoned, owned by a church. Although the film was shot in Pasadena, California, it was set in Illinois—so Carpenter and Cundey evoked the feel of the Midwest by carefully excluding palm trees from exterior shots and using the same several trash bags full of painted leaves for exterior scenes, scattering them around whatever street they were currently shooting on only to collect them all to be re-used in the next shot. Random people walking by were pressed into service as extras, the catering truck made a guest appearance in one scene, and the minimalist aesthetic carried over to post-production—Carpenter wrote the film's classic theme in only an hour, and scored the entire film himself in just three days.

It popularized Steadicam

The Steadicam is today one of the most ubiquitous camera rigs in film production, a status it owes at least in part to Halloween—even though it was a virtually identical but competing rig, Panasonic's Panaglide, which was actually used in the film. Both technologies feature body-mounted "floating" rigs that allow a camera operator to capture smooth, seamless tracking shots without using a dolly—ideal for Carpenter's vision for the film, which was to literally put audiences into the shoes of the killer.

The Steadicam had first been used by its creator, cameraman Garret Brown, in the 1976 film Bound for Glory. Halloween was only the fourth production to use the copycat system, which would eventually be all but forgotten as the Steadicam established itself and became a staple of modern cinema. Carpenter's long, ominous tracking shots inspired many a cinematographer to give the rig a try, and such moments as Rocky Balboa running up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art or the introductory sequence in Martin Scorsese's masterpiece Goodfellas may have looked very different had Carpenter chosen to shoot his little horror film differently.

Everybody worked for peanuts

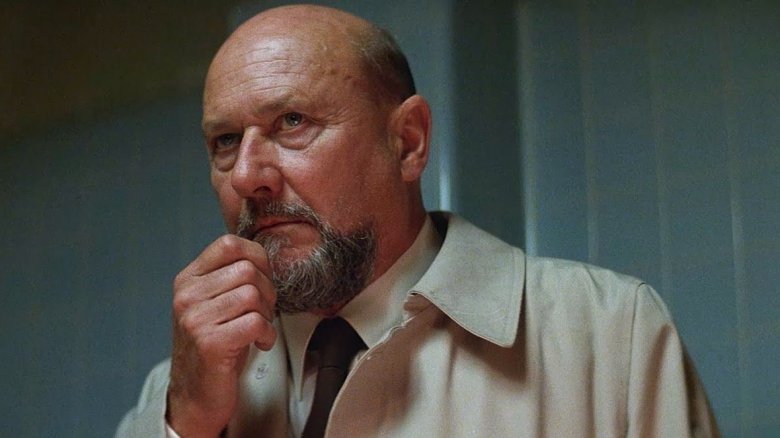

Carpenter wanted an established actor for the part of psychiatrist Sam Loomis, the only character in the film who understands the exact nature of the threat, and the part went to British actor Donald Pleasence. Carpenter was a huge fan—speaking with Deadline, he said he was slightly intimidated by their first meeting. "We were going to start the movie in a week or two, and he came to Los Angeles and I met him for lunch," he recalled. "He said, 'I don't know why I'm in this movie, and I don't know who my character is.' I was terrified... He said, 'The only reason I'm doing this movie is because I have alimony to pay, and my daughter in England is in a rock 'n' roll group and she said the music that you did for Assault On Precinct 13 is cool.' But it turned out great."

As the biggest name in the cast, Pleasence got a flat fee of $20,000, while nominal star Curtis received only $8,000. Carpenter's buddy Nick Castle—a screenwriter who would go on to pen Escape From New York and Escape from L.A.—was paid the princely sum of $25 per day to portray "The Shape," as Michael Myers is called in the credits, and Carpenter himself took only $10,000 plus a small percentage of the film's profits, which ended up working out for him. "I can't remember exactly how much money I made off the film," he said. "I do remember getting one check for over a million dollars—that wasn't bad."

Its initial release was very limited

Today, virtually all major studio films and a great deal of higher-profile indies open in wide release, hitting hundreds or even thousands of screens on the same day. But this wasn't so much the case in the 1970s, especially for low-budget independent affairs like Halloween. Films like these were often released in only a few markets, sometimes spending their entire runs there unless favorable word of mouth led to more engagements. This was certainly the case for Halloween, which debuted on October 25, 1978 in a single city—Kansas City, Missouri.

The film grew slowly out of this region—slowly enough, in fact, that for quite some time Carpenter assumed it had flopped. But as the buzz started to grow, national critics started paying attention—and they liked what they saw. The great Roger Ebert concluded his sparkling review with a warning that should have had any horror fan sprinting out the door to buy tickets: "I'd like to be clear about this. If you don't want to have a really terrifying experience, don't see Halloween." The film would go on to gross an astonishing $47 million, reigning for over a decade as the most profitable independent film ever made.

It's not gory at all

Because of its slow rollout across the U.S., many moviegoers heard about Halloween long before they got a chance to see it. This was the case with most indies at the time, but it had an interesting effect with certain horror films, a class to which Halloween certainly belongs: movies that are remembered for being far gorier than they actually are.

Most notably, 1974's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre contained surprisingly little gore for a film with that title, and in Halloween, there is virtually no onscreen blood. Carpenter's expert use of slowly building tension, spooky imagery, and perfectly deployed jump scares (such as the scene in which Laurie, pulling herself together after having just "killed" Michael, is painfully oblivious to his sitting up right behind her) left audiences with the impression that what they had just seen must have been crazily violent in order to be that disturbing. Hill alluded to this in production notes for 1981's Halloween II, saying, "People don't seem to realize that we showed next to no blood in the first picture. You think you're seeing a lot more than we're showing you."

There weren't supposed to be any sequels

Of course, nobody predicted Halloween would be a smash success—and as such, Carpenter and Hill never envisioned even a single sequel, let alone a franchise. "I didn't think there was any more story, and I didn't want to do it again," Carpenter explained to Deadline. "All of my ideas were for the first Halloween—there shouldn't have been any more... Michael Myers was an absence of character. And yet all the sequels are trying to explain that. That's silliness—it just misses the whole point of the first movie, to me."

This means that the film's famous cliffhanger ending—in which Michael is seen to have disappeared after being shot six times and plummeting off a balcony—wasn't intended to be a cliffhanger at all, but was simply meant to screw with audiences' heads. Halloween II was put into production as soon as it became clear how huge a success the first film was shaping up to be, but Carpenter and Hill had pitched producers a different idea—one which would have to wait until the sequel underperformed at the box office for them to briefly revisit.

It almost started an anthology series

Instead of finding ways to bring Michael Myers back, Carpenter and Hill had the idea to tell a different story with each new Halloween film, making it an ongoing horror anthology series. Halloween II's tepid box office convinced producers to give it a shot, and the result—1982's Halloween III: Season of the Witch—instantly polarized horror fans everywhere, and continues to do so today.

The film focuses on the sinister Silver Shamrock Novelties corporation, manufacturers of the most popular children's masks of the season—which are central to a nefarious plan to wreak untold carnage on Halloween night. Carpenter and Hill produced, leaving directing duties to none other than Tommy Lee Wallace, who had pulled quadruple duty on the original film. But the film's insane sci-fi/horror story landed on extremely confused audiences, who were expecting far fewer sinister corporations and much more Michael Myers.

They would get their wish six years later, although the sequels and rebooted series that followed would provide mostly diminishing returns, with one exception—1998's Halloween H20: 20 Years Later, which ignored previous sequels and served as a direct sequel to Halloween II. Ironically, it's about to receive the same retcon treatment—the Halloween reboot scheduled for 2018 will ignore its predecessors and serve as a direct sequel to the original, with Carpenter serving as executive producer and providing the score—and Jamie Lee Curtis returning to play Laurie Strode one more time.