Movie Endings That Don't Mean What You Think

Movies are a subjective medium, often taking on different meanings and interpretations depending on the viewer's own experiences. An ambiguous ending or tonally divergent scene can be a head-scratcher for audiences, but we've got some explanations to help satisfy your curiosity. Beware, however: spoilers ahead.

Total Recall

Combining the brainy science fiction concepts of Philip K. Dick with the irreverent, hard R-rating stylings of director Paul Verhoeven should be a recipe for disaster, but 1990's Total Recall has become a cult classic in the decades since its release. Adapted from Dick's short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale," the film centers around Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger), a construction worker who may or may not be a secret agent with memory loss, and a rebel war on Mars in the near future.

The film continually encourages audiences to question the reality of what they're watching. Are you actually seeing Quaid finish his secret mission, or is this part of the Rekall procedure? One moment near the end of the film seems to point the direction squarely towards the latter explanation.

Early in the film, before the Rekall procedure has started, a lab tech reading Quaid's dreams notes that they include "a blue sky on Mars." While the similarities of Melina (Rachel Ticotin) and the woman in Quaid's dreams can be explained away by his buried memories, the lab techs are clearly surprised by his conception of a Mars with a blue sky. When the movie ends with Quaid and Melina looking over the Martian sky, newly blue from oxygen after saving the planet in a grand adventure, it's the biggest clue to the viewer that we're watching a dream.

In Bruges

In this darkly comic morality tale, Ray (Colin Farrell) and Ken (Brendon Gleeson) are two assassins sent to Bruges ("It's in Belgium") to lay low after a hit gone wrong. By the end of the film, half the cast is dead, and Ray is being carried away to an ambulance, hoping he doesn't die, and thinking about the nature of Hell. Viewers are left to wonder: Did he die? Did he live? Did he go to jail for beating up the Canadian couple?

In one reading of the film, none of those questions matter, because Ray is in Purgatory. Earlier in the film, Ken takes Ray on an arts tour of Bruges, culminating in the two of them viewing Hieronymus Bosch's "The Last Judgement." It's the one part of the tour that Ray actually seems invested in, and it sparks a conversation about Purgatory, a place for people that "weren't really s***, but... weren't all that great either."

The final scene of the movie is an aesthetic match for Bosch's painting, as Ray looks up at mysterious animal-faced creatures (actually just actors in costume), while he wonders what punishments await him. Ray committed a horrible sin by accidentally killing a child, but he ends the movie wanting to live to atone for his mistake. He thinks Bruges is Hell, but maybe it's just a place for people not quite bad enough for the real thing.

Fargo

Fargo ranks among the simplest of the Coen brothers' films; it's the story of a small town crime, a greedy little man with too much ego, and a rural sheriff with a good heart and a keen wit. Still, while most viewers remember Steve Buscemi's performance, the surprisingly grim body count his character racks up, or his gruesome disposal in the wood chipper, the movie's ending is ultimately a quieter scene. Sheriff Marge (Frances McDormand) and her husband Norm (John Carroll Lynch) are shown laying in bed as he laments his mallard painting being passed over for the first-class stamp contest. Margie responds that they're "doing pretty well, Norm."

The ending completely encapsulates the core themes of the movie, and refutes the naked greed of nearly every other character. From Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy), whose ambitions lead to the deaths of nearly half a dozen people, to Mike Yanagita's (Steve Park) desperate desire for Marge to believe that his life is better (or at least more appealingly tragic) than it seems, the characters in Fargo find that they sow chaos when they focus on what they want rather than what they have.

Marge's confirmation of the good life she and her husband have built together changes the movie from a comedy-drama (or dramatic comedy, no one's quite sure) into a morality play, reminding the audience to be grateful for what they have.

Get Out

The story of Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), a black man meeting his white girlfriend's parents for the first time, Get Out borders on a cringe comedy at times, but the horror only increases by the minute. By the end of the movie, Chris has escaped the grounds of the Armitage mansion with his friend Rod, after killing the family and burning their secret brain-swapping laboratory.

The last line of the movie is Rod telling Chris that he can "Consider this situation f***ing handled." But Chris doesn't respond to Rod, instead just looking sadly out the window as they drive away, leaving Rose (Allison Williams) to die in the street behind them. While it's cathartic to see the hero of the film survive, defeat the villains, and drive off with his friend, the ending is a bit darker than people realize: Chris knows the situation isn't "handled." Logan (LaKeith Stanfield), a victim of the procedure shown earlier in the film, is still being mind-controlled, along with another few dozen old, white gentry that are still stealing black bodies and minds.

In the alternate ending, this meaning is made much more explicit. Chris winds up in jail for the murder of the Armitage family, with no way to prove his innocence or expose their crimes. He tells Rod that at least he "stopped it" as he's led to jail, where he's surrounded by other black men. In both endings, racism isn't vanquished just because Chris is able to defeat the rich body-snatchers; they were just one particularly repugnant example of a systemic—and very real—horror.

Videodrome

Director David Cronenberg pioneered a new wave of body horror with practical effects and eerie, visceral set pieces—arguably best exemplified in 1983's Videodrome, which came hot off the heels of Cronenberg's most commercially successful film, Scanners, and almost seemed willfully antagonistic towards the audience that would be viewing it.

The story centers around Max Renn (James Woods), the president of a Toronto television station that produces programming pushing the boundaries of good taste. Obsessed with escalating his network's output of sex and violence, Max finds a mysterious broadcast that eventually embroils him in a tangled web of body modification, sadomasochism, and conspiracies.

The film ends with Max raising his hand—which is now a flesh gun—to his head and intoning, "Long live the new flesh." The line is echoed throughout the film as a reference to a new breed of humanity, one that will have "special names" and live out their lives through screens. When Max shoots himself, he's mirroring the life and death of O'Blivion, another character who died and lived on through recorded media.

Max becomes the "new flesh" through the movie the audience watches, Videodrome becoming a meta-textual artifact of the Videodrome network. Max doesn't kill himself at the end of the movie because he can't die—he's become the new flesh through the viewing of the movie; the audience an automatic participant in his ascendence. Pass the popcorn.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

As the continuation of David Lynch and Mark Frost's seminal television series Twin Peaks, the 1992 big-screen prequel Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me had a lot to live up to. The movie expands the world of the show, introducing new characters and delving deep into the personality of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) in the week before her murder—the instigating event for the show.

The movie's as Lynchian as it gets, with a David Bowie cameo, a shrieking, mask-wearing child, and the audience's creeping realization that they're watching a character walk methodically to their inevitable death.

The last shot follows a viscerally unpleasant murder scene with a shrieking sound design, so it's no wonder many viewers thought of it as an unpleasant horror ending. But as TalkFilmSociety critic Andrew Ihla argues, it's also possible to view these closing moments as ultimately happy ones for Laura. "Lynch leaves us with a powerful, wordless moment of Laura waking in the Red Room, Dale's comforting hand on her shoulder," writes Ihla. "And the angel from her painting—the symbol of innocence and light that had literally vanished from her bedroom when she was at her lowest ebb of self-loathing and depression—made real and shining down on her."

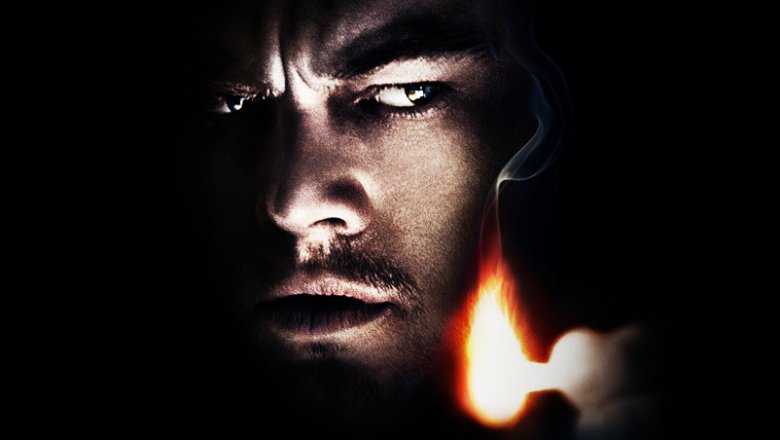

Shutter Island

Shutter Island, the Martin Scorsese adaptation of Dennis Lehane's novel of the same name, is a period piece thriller with a murderer's row of excellent actors from Leonardo DiCaprio to Max von Sydow. In 1954, U.S. Marshall Teddy Daniels (DiCaprio) investigates an insane asylum following the escape of notorious murderer Andrew Laeddis while dealing the suspicious Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsley) and a disappearing partner (Mark Ruffalo).

The central twist of the movie—that Teddy Daniels is actually Andrew Laeddis, acting out a therapeutic role play to restore his memories following the murder of his wife after she drowned their children years ago—drew most of the audience's attention, but the enigmatic final line of the movie has confused audiences well beyond the credits.

Teddy, seemingly regressed back to his original delusion that he is a U.S. Marshall, asks Chuck Aule (Ruffalo), "Which would be worse? To live as a monster or to die a good man?" before he walks purposefully towards the lobotomists. According to Scorsese's psychiatric advisor on the film, James Gilligan, the line is Teddy faking his own regression, choosing a quasi-suicide to atone for the murder of his wife. According to Gilligan, the last moments of the film are Teddy saying, "I feel too guilty to go on living. I'm not going to actually commit suicide, but I'm going to vicariously commit suicide by handing myself over to these people who're going to lobotomize me."

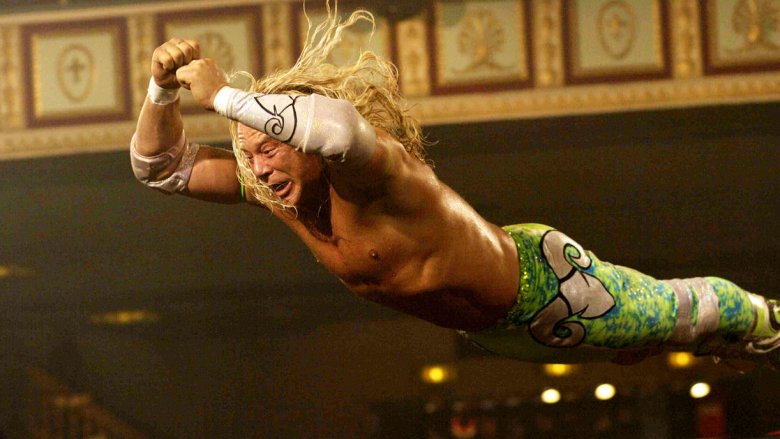

The Wrestler

Darren Aronofsky's film about a washed-up wrestler who comes back to the job that once made him famous—starring Mickey Rourke, a washed-up actor making a comeback in the job that once made him famous—is fairly straightforward. Robin Ramzinski (Mickey Rourke) still longs for the stage, and struggles to deal with the fallout from decades of poor choices while trying to reconnect with his estranged daughter.

The movie ends with Ramzinski preparing to do his signature move on his opponent, well aware of the health risks and the possibility that he might die in the ring. The last frame of the movie shows him leaping out of the frame—whether he hits his opponent, or even lives, is left unclear.

In his final speech to the crowd, Ramzinski says, "The only one that's going to tell me when I'm through doing my thing is you people here." While the cheering continues for a couple of seconds after he leaps out of the frame, the movie ends here, and the audience—both in the movie and The Wrestler's real-life viewers—will leave. Ramzinski was a character who only felt alive when he was in the ring, so it's fitting that it's where he dies, too.

Primer

Often considered one of the most complicated science fiction movies ever made, Primer centers around Abe (David Sullivan) and Aaron (Shane Carruth), two men who accidentally invent a time machine and resolve to understand what they've created. While it sounds simple, the movie rapidly cycles into different timelines and body doubles with no onscreen explanation. It's no wonder that most viewers were confused by the ending, in which a double of Abe accompanies a double of Aaron to an airport, promising to protect Aaron's family from... someone, while another Aaron double calls yet another double of Aaron mumbling a cryptic warning. Simple, right?

This detailed timeline of the movie which helps at least explain how many copies of Abe and Aaron are onscreen in the last five minutes. For a simpler explanation of what happens when two scientists invent a time machine, it may be pertinent to quote Jurassic Park: "Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

The Third Man

Arguably one of the best American noir films ever made, Orson Welles' The Third Man follows a pulp Western writer, Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton), as he arrives in Allied-occupied Vienna to see an old friend, Harry Lime (Orson Welles), and tries to uncover a conspiracy of racketeering, police corruption, and betrayal. By the end of the film, Lime is dead by a police bullet, and Martins is preparing to leave Vienna.

The film's final shot is of Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), Lime's ex-girlfriend and Martins' de facto love interest, as she methodically walks by Martins, completely ignoring him, seemingly furious at him for the role he played in Lime's death. While a grim ending is often part and parcel of film noir, the ending actually has a larger thematic connection to Martins' arc.

Martins spends the film threatening to write a book about his treatment in Vienna at the hands of the military authorities, at one point referencing the movie's title as a possible name for the unwritten work, and he seems to think of his experiences as one of his pulp novels. Even as the film's tone turns dark and Lime reveals the depths of his evil, Martins continues to act like a righteous pulp hero. It's only with the last shot, as the damsel in distress chooses to walk by Martins, likely to deportation and possible death, that he realizes the depths of his ignorance. Life isn't one of his Westerns: sometimes the villain's death doesn't make everything better for everyone.