That's What's Up: Learning To Love Jack Kirby

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What makes someone suddenly go from disliking Jack Kirby to realizing how great he is? It seems to happen to a lot of people. — @barelysushi

By any imaginable measure, Jack Kirby is the single greatest comic book creator who's ever lived. Working alone or with collaborators like Joe Simon and Stan Lee, he created or co-created... well, everything. It's not just a matter of characters, although the roster of heroes and villains Kirby's responsible for includes Captain America, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, the Avengers, Darkseid, Etrigan the Demon, Mr. Miracle, the New Gods, Devil Dinosaur, OMAC, and a couple hundred more. It's the approach to storytelling, the endless influence that allowed for cosmic space operas and bare-knuckle street fights all happening at the same time.

But for some readers, it takes awhile to realize that. As much as it's possible to recognize his contributions, actually learning to like his work can be a little more difficult. Or at least, that's how it happened with me. The first time I read a Jack Kirby comic, I hated it—but a lot of that probably has to do with how and when I encountered it.

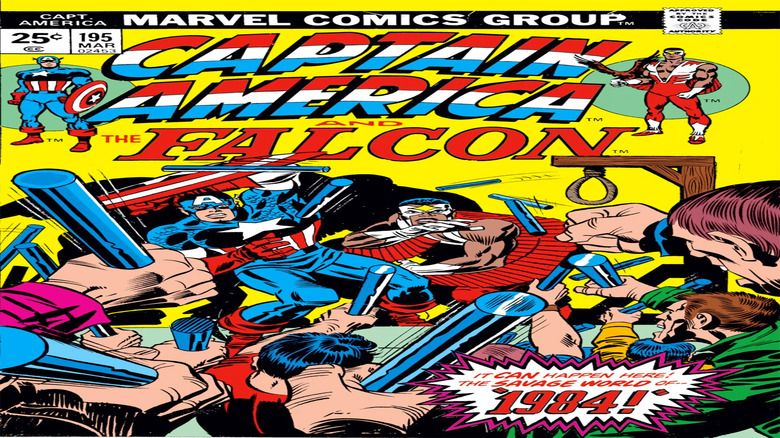

Captain America #195

My first experience with Kirby came from a beat-up copy of Captain America #195. I have no idea how I got it, since it was published about seven years before I was born, but at the age of six, I wound up with it mixed in with the stack of Batman and Superman comics that I'd picked up at the convenience store across the street from my grandparents' house.

If you're not familiar with the issue, it comes near the start of Kirby's mid-'70s return to Marvel and the epically bombastic "Madbomb" storyline. It took the themes of battling against tyranny and fascism that had been built into Captain America from the very beginning and took them to a truly bonkers extreme, weaving an adventure that saw Cap and the Falcon dealing with a sinister weapon that could drive people insane with hatred, leveling whole cities with the resulting riots—which itself turned out to be a plot from a secret group of secessionists who wanted to reunite America with the United Kingdom so they could take their place as a ruling aristocracy. Along the way, they wind up dealing with a deadly underground roller derby, a small army of misshapen mutants, and, perhaps worst of all, Henry Kissinger.

In other words, it rules. That first time I read it, though, I wasn't blown away by Kirby's trademark wild ideas and over-the-top execution.

I was terrified.

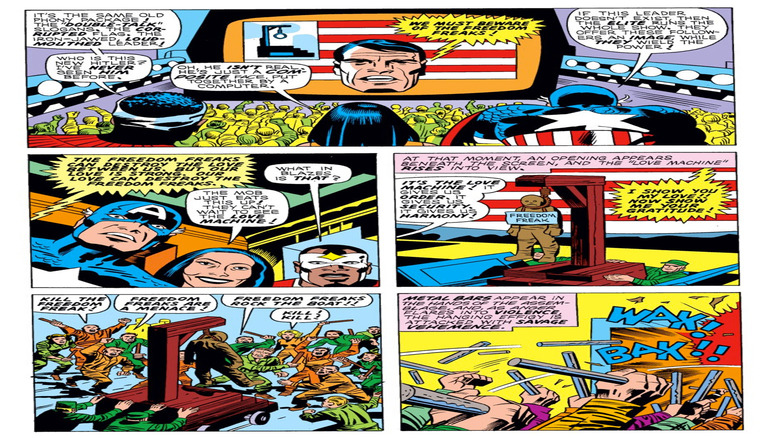

The Love Machine and the Freedom Freaks

The scene where Cheer Chadwick—would-be princess of a conquered United States Aristocracy—just casually explains the way her father and his organization have riled up otherwise ordinary Americans into a bloodthirsty mob that was willing to tear a "freedom freak" limb from limb was burned indelibly into my brain. I'm not even sure if I finished the issue, but if I did, I doubt it made me feel any better, since this one ends with Cap getting knocked out by a roller derby killer named Tinker Bell while an unseen mastermind confirms he's going to destroy freedom forever.

I have the distinct memory of sitting there, holding this comic, and thinking "wait a second... but I like freedom!" and feeling a genuine sense of danger that the people in this comic were going to come to my house and beat me up with clubs. Admittedly, I was a very impressionable and extremely high-strung child, but still, the fact that I was legitimately worried about that speaks to just how effective a storyteller Kirby really was.

But that fear, combined with my instant aversion—maybe even revulsion, if we're honest with each other—to the exaggerated forms and wild-eyed expressions of Kirby's artwork, led me to put that comic at the bottom of a stack underneath a bunch of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Adventures and never return to Kirby for years. I'm not the only one who felt that way, either: my writing partner, Chad Bowers, was a little more intrigued by Kirby than I was, but he used to tell his parents that he wanted "those ugly comics" when they went to the comic book store.

Lee (not that one) vs. Kirby

My second experience with Kirby didn't really go much better, although it was certainly less frightening.

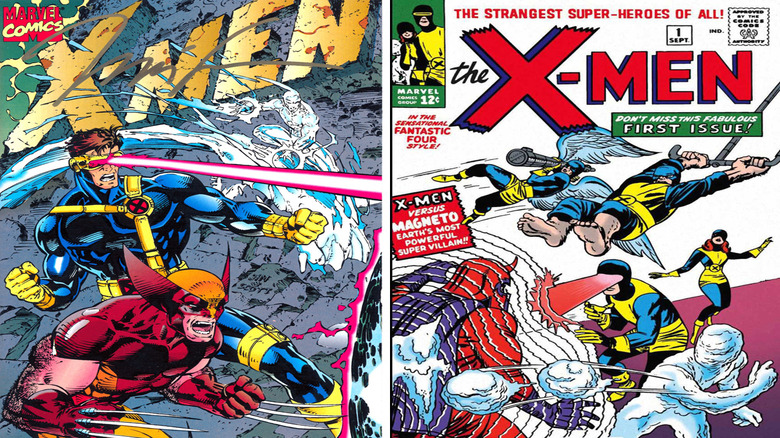

In the '90s, Marvel decided to take advantage of the massive popularity of the X-Men by reprinting some of their earlier adventures in the form of a monthly series. It was something they'd done before with Classic X-Men, a title that reprinted the groundbreaking work that Chris Claremont, Dave Cockrum, John Byrne, and Terry Austin had done in the '70s, often adding new backup stories that fit between the issues and added a little bit of additional fun. Like, say, Misty Knight fighting a shark.

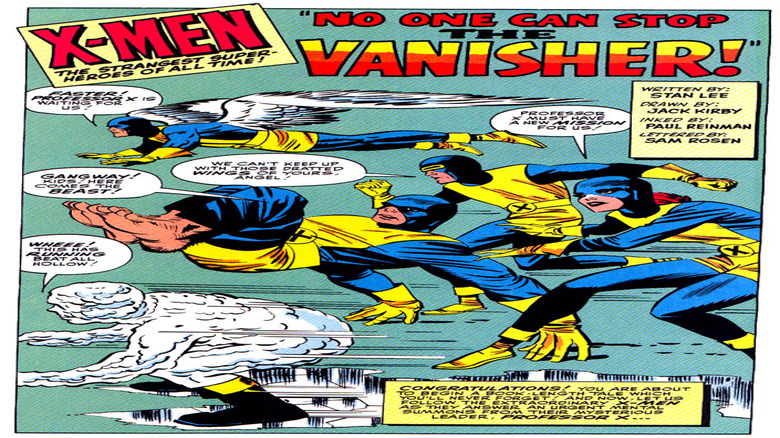

For X-Men: The Early Years, though, they went all the way back to the beginning in 1963, and reprinted Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's original stories about the Strangest Teens of All fighting villains like Magneto, the Vanisher, and the Blob. Unfortunately, the audience that was being brought to X-Men in the early '90s wasn't really there for Kirby. The aesthetic that had propelled the X-Men to massive popularity and five successful seasons on Saturday morning television came not from Kirby's lumpy uniformed teens, but from Jim Lee's grimacing, statuesque '90s superheroes.

Kirby's X-Men

Of course, it's also worth noting that the original X-Men was, to put it charitably, not Kirby's best work.

While books like Fantastic Four saw Kirby and Stan Lee producing a virtuosic masterpiece that provided the blueprint for modern superhero epics—and while Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and, later, John Romita's work on Amazing Spider-Man is probably the most influential run on comics since Superman kicked off the superhero genre in 1938—X-Men was arguably the weakest title of the entire lineup. To say that it feels phoned in isn't quite accurate, and it certainly has its charm, but it's easy to see why X-Men languished while the other books took off, eventually becoming a bimonthly reprint book before Len Wein and Dave Cockrum made a last-ditch effort to revive the team by creating an "All-New" international version that featured new characters like Storm and Nightcrawler, along with a weird little Hulk villain called Wolverine.

And we all know how that went.

Point being, while those early issues are historically important, they're not really that great, and certainly don't have the same feeling that you get from later stories. Heck, I'd go as far as saying that pound for pound, they're not nearly as good as the other team of merry misfits led by a dude in a wheelchair that also debuted in 1963 over at DC: Arnold Drake and Bruno Premiani's Doom Patrol. Given how closely they debuted (and how small the comics creator community was in New York at the time), there's been a lot of speculation about who ripped off whom, but at the end of the day, it's pretty clear that one of those books is much more fun to read, even if the other one spawned a franchise.

OMAC #2

So yeah, even though I was constantly reading comics that were influenced by him and featured characters he'd created, my experience with Kirby itself amounted to two strikes. And then one day it happened: I found the book that made it all make sense, the key that unlocked Jack Kirby for me.

I'm embarrassed to say that it took until I was in my early 20s, when I was working at a comic book store. At the time, thanks largely to the fact that the shop had a huge stock of dirt-cheap back issues and a steep employee discount, I was diving into stuff I'd either never read or had initially dismissed, runs like Justice League International and Suicide Squad that would become some of my favorites. And one day, on a whim, I cracked open a copy of OMAC #2.

OMAC is one of Kirby's more obscure comics, originally published in 1974 while he was working at DC, and only running for eight issues before he returned to Marvel and Captain America. It works with the same themes, too, essentially functioning as a dystopian, post-apocalyptic spin on Cap, where frail weakling Buddy Blank is transformed via "electro-hormone surgery" into the unstoppable super-soldier OMAC (the One-Man Army Corps). And when I say "unstoppable," I mean it: the first page of the second issue involves OMAC being told he can't enter a city that's been rented out by the super-rich. The second page? Well, have a look for yourself.

'This dude is a one-man army!!!'

I love that page. The sheer energy, the fact that it escalates from "produce an invitation or take off" to a giant man with a mohawk just blasting his way through nine dudes with a single punch. And the best part? That one poor guy who has a hold of his foot, just screaming from off-panel as OMAC wrecks shop.

I'm not going to lie, it was the over-the-top action that hooked me. There are very few things in this world that I love more than a ridiculous action sequence, and this is one of the biggest I've ever seen. The more I read through the series, though, the more fascinating it became. It wasn't just a rip-roaring adventure, it was a weirdly prescient story about the anxieties of the future that manifested themselves in ways that, even 40 years later, felt like they were still relevant.

OMAC himself, for instance, was created because he lived in a time when full-scale war was so dangerous committing to a large conflict could mean the end of the world. That's the kind of apocalyptic fear you get from a lot of media created at the height of the Cold War, especially when the creators were—like Kirby—World War II veterans who'd seen firsthand the horrors of a global conflict. OMAC, however, goes beyond that. His enemies aren't just the tyrants and fascists that Captain America would fight, they're the super-rich, the opportunists who use their privilege to exploit the workers beneath them. They're the people who sell their fellow citizens a bill of goods, fake friends that come in boxes and profess love for their owners, distracting them from plots to harvest their youthful bodies or hold water for ransom.

There's even a text piece in the first issue where Kirby talks about how rapidly the world is changing because computers are talking to each other over long-distance networks. In 1974.

The Fourth World Saga

That's where it all clicked, where I really got Jack Kirby for the first time. It wasn't just the energetic artwork and bombastic storytelling that just simply did not have time for subtlety—although honestly, those are the elements that you have to be prepared for if you're going to sit down with some of his work—it was the way he used that approach to take forward-thinking, easily relatable ideas to their almost limitless extremes.

It's one of the reasons I'll always prefer Kirby's work in the '70s, when he was writing and drawing his own comics (and producing them at a truly incredible rate of a complete issue every two weeks) to the '60s stuff. Books like Fantastic Four may have been the foundation, but everything that comes after he jumps ship to DC is pure Kirby, these unfiltered ideas jumping directly from his head to the page.

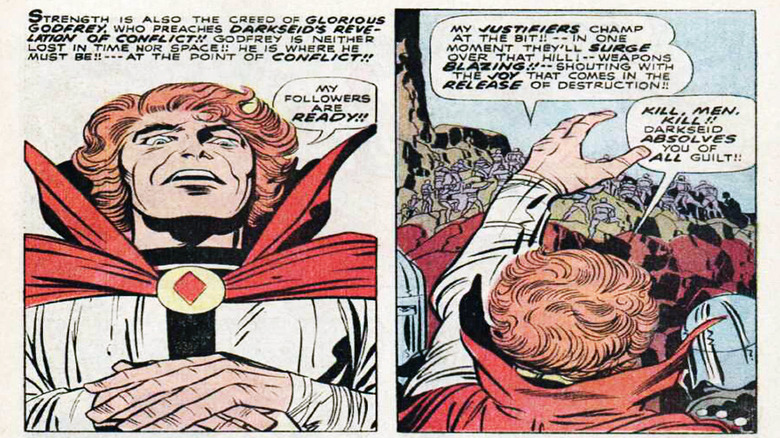

From OMAC, I went to New Gods and the Fourth World saga, a morality play spread across a crackling cosmos where the villain is literally the dark side of our own personalities who tempts us into blind obedience and a hatred of each other that's rooted in a hatred of ourselves. It's a saga where the worst thing you can do is justify your own cruelty to another, and where that impulse is far too easy to fall into. It's about good and evil, but in a mythology where good and evil aren't equal and opposite, where evil inevitably falls short of the potential of good, but always has to be kept in check.

Devil Dinosaur

Of course, not everything has to be a treatise on the nature of morality and vigilance against those who would lead us down the path of tyranny. OMAC also led me to books like Devil Dinosaur, another product of Kirby's return to Marvel that featured cavemen hanging out with dinosaurs and a text piece in which Kirby shrugged off that idea's impossibility by saying it took place in "The X-Age," a time when we can never really know for sure what happened due to gaps in the historical record.

Then, like six issues after he debated the scientific accuracy of a story about a giant dinosaur stomping on people, he revealed that the Tree of Knowledge (you know, from the Bible) was actually a computer from an alien spaceship. Because, you know, why not?

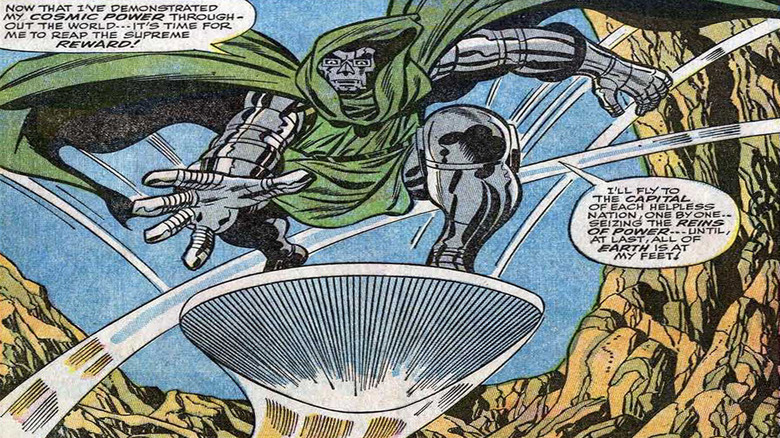

That led me in turn to Silver Star, a latter-era take on the Captain America formula, and then to working backwards into the Marvel stuff. Fantastic Four was the one that took me the longest to get around to, but when I finally did, it showed how ahead of the curve Kirby and Lee were, dealing with slightly more sophisticated themes than what you were likely to find in, say, the Batman comics of the mid-'60s. Especially when it came to Dr. Doom.

Dr. Doom

There's a lot of good stuff in Fantastic Four, including the Galactus Saga laying the foundation for the modern Event Comic, the introduction of Black Panther, and virtually every single thing about Ben Grimm, but the all-time champion is Doom. He is the best villain, driven purely by hate, with a design that has remained virtually unchanged since he made his debut in 1961.

Now, 15 years after having that revelation, I've read every scrap of Kirby comics I can get my hands on, from the mainstream epics to obscure one-offs like The Dingbats of Danger Street to scraps of unfinished projects like his unproduced adaptation of The Prisoner. There's something rewarding and fascinating about each one, whether they have that operatic capital-I Importance to them or not.

As for what makes it happen, I'm really not sure. I'm tempted to say that you don't really get Kirby until you develop the ability to look beyond the surface of a story and see how much craftsmanship it takes to look as simple as his comics, but that's really just covering up my own initial revulsion. There were plenty of kids who encountered Kirby at the same age I did and wound up loving him from the start; I'm just a slow learner.

But I do think there's something to the idea that it just has to hit you right for everything to make sense, and once you're there, you're there forever. And the good news is that Kirby's contributions to the medium are so vast, so unavoidable even a quarter-century after his death, that even just scratching the surface of superhero comics means you're encountering them all the time.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."