How Homecoming's Spider-Man Is Different From The Comics

Spider-Man: Homecoming has been warmly received by fans and critics, thanks in no small part to Tom Holland's pitch-perfect portrayal of the web-slinger and his nerdy alter ego Peter Parker. Given the near-unanimous agreement that Holland captures the spirit of the character, it's interesting to note some of the significant differences between the Spidey of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and his comic book counterpart. Some of these changes serve to help Parker fit more snugly into the sprawling MCU, while others are necessary updates from the character's '60s origins. Here's a look at the differences between Spider-Man in the comics and the big screen, and beware—spoilers for Spider-Man: Homecoming abound.

Peter's webbing

Like comic book Spidey, MCU Spidey uses "web fluid" of his own design. It's a versatile substance, as shown when Tony Stark comes up with several hundred interesting variations on its usage, but it may take MCU Parker awhile to perfect the formula. Comic Spidey's formula is not only more developed, it's considerably stronger, as seen in a one-panel at the end of Amazing Spider-Man #1. The issue's writer, none other than Stan Lee himself, used the Fantastic Four to illustrate the webbing's properties: it's almost as stretchy as Mr. Fantastic, "90% fire (and Human Torch) proof," and if its thickness were increased to a mere half-inch, "one strand would be enough to hold the mighty-muscled Thing a prisoner for life!"

Depending on the writer and time period, the tensile strength of Spidey's web in the comics consistently ranges from "off the charts" to "WAY off the charts." By comparison, MCU Spidey's webbing is shown breaking down relatively easily, and of course only a two percent margin of error was enough for his attempt at holding the Staten Island Ferry together to totally fail. We do see in the film that Peter is still working on revising the formula, but he may need a little (more) help from his genius-billionaire-playboy-philanthropist benefactor—because MCU Parker isn't quite the brain that comic Parker is.

Intellect

The MCU's version of Peter Parker is obviously very, very intelligent. He's among the smartest in a school full of smart kids, he synthesized the aforementioned web fluid from chemicals common enough to be found in his chemistry classroom, and he was able to defeat a highly advanced security system with nothing but his brains and the time required for 200-plus attempts. All very impressive, to be sure—except in comparison to his comic book counterpart.

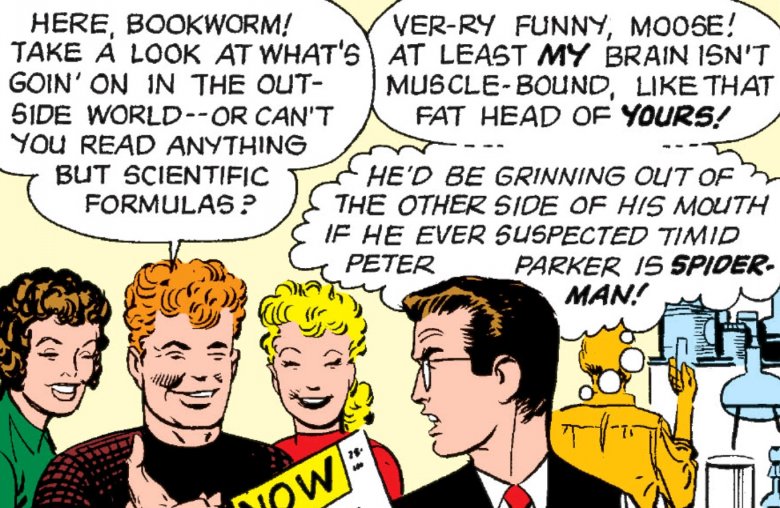

While MCU Parker isn't even the president of his academic decathlon team, in the comics, he's one of the most intelligent people in the Marvel Universe, even as a teenager. To his high school classmates, his braininess was practically his only defining characteristic, and in more recent years, his intellect has grown to rival the sharpest minds in the world—up to and including the likes of Stark, Hank Pym, Reed Richards, and Bruce Banner. He's even pulled a Pym-like trick by discovering "Parker Particles," a completely new form of energy which almost caused a citywide catastrophe—which Parker was then able to avert by using some alien tech. MCU Parker has a lot of catching up to do, and with so many other big brains in his universe, it seems unlikely that his future adventures will put a spotlight on his abilities as a scientist the way the comics have.

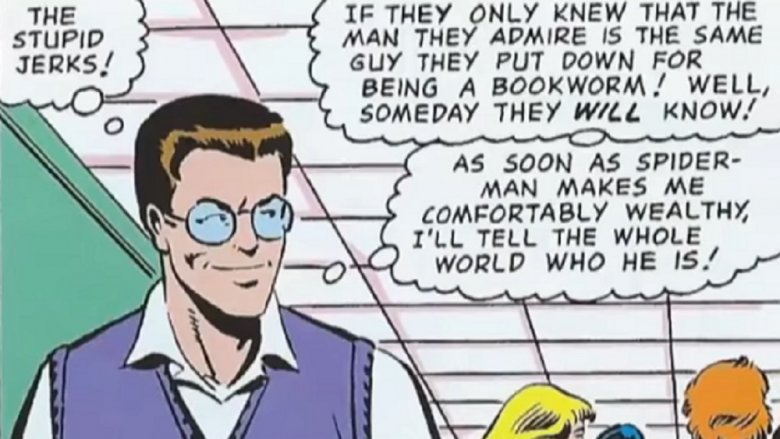

Not-so secret identity

The comic book version of Peter Parker goes to absolutely insane lengths to prevent his secret identity from being revealed. Fortunately for him, virtually every time he gets caught with his mask off, nobody believes that puny Parker could really be Spider-Man. The Green Goblin manages to learn his identity but forgets it, and on more than one occasion Parker is able to throw off suspicion through clever means, such as convincing J. Jonah Jameson that photographic evidence has been forged. Only Wolverine (who can identify him by his scent) and Daredevil (who can identify him by his heartbeat) learn his secret—but MCU Parker isn't quite as cautious.

For starters, let's not forget that Tony Stark was able to deduce his identity without breaking a sweat. Parker has his Stark-enhanced suit for practically no time at all before he's caught in it by his best friend Ned. Deadly rival Adrian Toomes, a.k.a. the Vulture, is able to figure it out from a few random comments made by his daughter Liz, and MCU Parker closes out his first solo adventure by carelessly letting his Aunt May—whom comic Parker protects his secret from most fiercely of all—walk in on him while in costume. After a start like this, it's hard to imagine MCU Spidey's identity remaining any kind of secret at all for much longer.

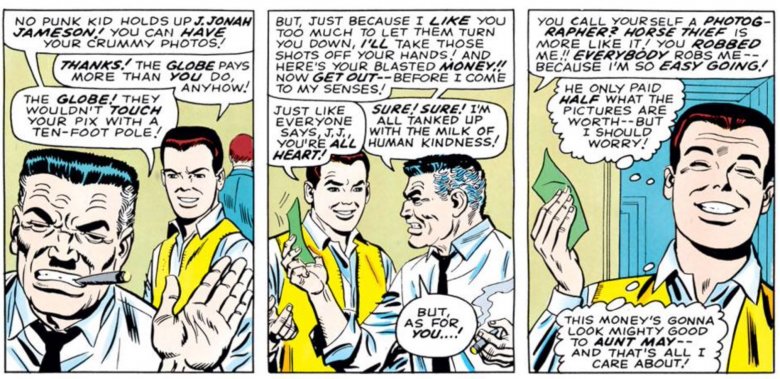

No pictures, please

Another of Parker's defining traits in the comics is his career as a photographer. He was an avid shutterbug even in high school, using his Uncle Ben's old camera to snap his first freelance pics—of the Vulture—in Amazing Spider-Man #2. His antagonistic relationship with Daily Bugle editor J. Jonah Jameson, who famously considers Spider-Man a menace, is the stuff of comic cook legend—and more than one super-powered battle has trashed the Bugle's offices over the years.

Parker's ever-present camera was conspicuously absent from Homecoming, as were any mention of Jameson and the Bugle, even in passing. J.K. Simmons, who played the role of Jameson to perfection in Sam Raimi's Spider-Man series, had lobbied to reprise it in Homecoming—but any hopes of this happening were dashed when Simmons was cast as Commissioner Gordon in the upcoming DCEU Justice League crossover. For now at least, Parker's freelance photography career—as well as New York's most famous Spidey-hating tabloid—doesn't appear to be coming into play for the MCU version of the character.

Updated high school and family dynamics

One of the reasons Spidey resonated so strongly with comics audiences of the '60s was the character's grounding in the real-life problems of teenagers. Peter Parker was a bullied loner, unsure of himself and terrible with girls, with weighty family responsibilities in the form of a frail and elderly aunt. MCU Spidey is similarly grounded in the world of a real teen, but Homecoming updates the dynamics of high school and family life in a way that neither of the previous film series did.

MCU Parker might get picked on a bit, but not like his poor comics counterpart. The bullying in Homecoming is much more subtle than being called a bookworm and getting shoved into lockers, highlighted by Flash Thompson's transformation from dumb, strapping jock in the comics to smug rich kid in the film. Also in keeping with the modern setting, relationships between peers and family are a little more complex than those seen in the comics. Female peers aren't automatically potential love interests (as every female character in the comics seemed to be), and Aunt May is the age you would expect the aunt of a 15-year old kid to be, rather than being depicted as elderly. All of these changes are totally appropriate for a fresh take on decades-old source material, and serve to make MCU Parker even more relatable to young audiences.

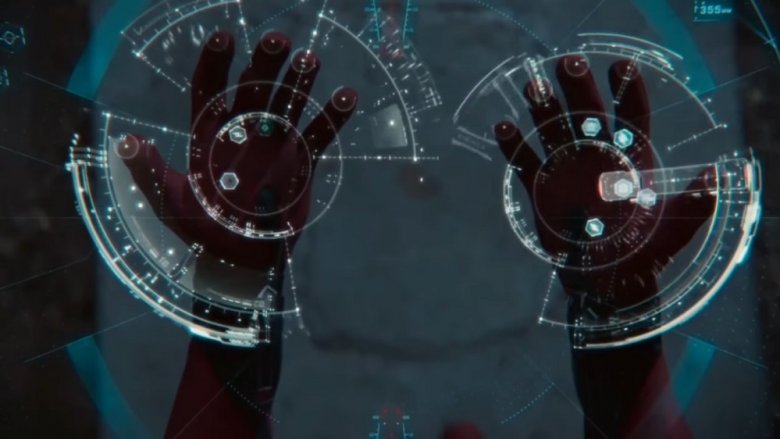

Stark Tech

In the comics, Spidey isn't a stranger to tech assistance, but he's often on his own when it comes to inventing it—especially in his early years. The first Spider-Man comics had Parker inventing not only his web fluid but Spider Tracers (tiny spider-shaped tracking devices, which receive a shout-out in Homecoming), and outfitting his costume with such meager bells and whistles as a belt-mounted spotlight and a special camera. MCU Parker's Stark-augmented suit is a far cry from any tech comic Spidey had available to him for decades.

MCU Parker's tech enhancements are likely to be a fixture, owing to his relationship with Stark. If there's one thing we know about Stark, it's that he never stops upgrading, and the shiny new suit Parker turns down at the end of Homecoming probably won't stay in storage for long. Speaking of which, sharp-eyed fans noticed a few aesthetic similarities between that suit and a couple of others which have appeared in the comics: the Iron Spider, which Stark built for Parker during the Civil War storyline, and the Spider-Armor, which Parker designed himself.

Temper and moodiness

Perhaps because it was created in the '60s when teenagers were like aliens to most adults, comic book Parker was a bit of a hothead. He was prone to fits of self-pity and depression, and his internal monologues were often as full of self-doubt as his external ones were full of scathing wit. He almost hangs up his costume as early as Amazing Spider-Man #3 after being soundly beaten by Doctor Octopus, and he doesn't really play well with others at first, regularly showing flashes of anger and outright arrogance.

Comic book Parker almost makes enemies of the Fantastic Four in the very first issue of Amazing Spider-Man, angling for a spot on the team—and their "top salary"—by breaking into the Baxter Building and picking a fight. He's uncomfortably obsessed with money even after the failed entertainment career that indirectly resulted in the death of his Uncle Ben, and as moody as any '60s adult would expect the average teenager to be.

MCU Parker, by contrast, is insanely well-adjusted. He shrugs off taunts from Flash Thompson, has a close and warm relationship with May, and is respectful of his fellow superheroes to a fault even while being forced to fight them. It's a welcome change, and a testament to Tom Holland's talent that he can so effectively evoke the essence of the character without being the bratty teen that comic book Parker often was.

Rogues' Gallery

Spider-Man has one of the deepest and craziest rogues' galleries in all of comics, so despite five previous films—more than one of which suffered from serious villain bloat—Marvel and Sony won't run out of interesting threats for MCU Parker to face. But he might not soon, if ever, see any of comics Spidey's most iconic villains, for more than one reason.

Marvel mastermind Kevin Feige has said that at least for the foreseeable future, the studio intends to stick to villains that haven't been seen onscreen before—which would remove a huge chunk of comic Spidey's rogue's gallery from consideration, including arch-nemeses Green Goblin and Doctor Octopus, as well as the Lizard, Electro, the Rhino, and of course Venom—for which Sony Pictures is developing a vehicle in a separate project that will stand apart from the MCU. Feige has also stated that, although nothing has been ruled out, there are no immediate plans for any of the MCU's films to cross over with their Netflix series in any meaningful way. This means Wilson Fisk/Kingpin, one of comic Spidey's deadliest enemies, may also never cross paths with the MCU version—unless Vincent D'Onofrio, who portrays Fisk on the Netflix series Daredevil, has anything to say about it. (Unfortunately, he probably doesn't.)

Relationships

As with some of comic Parker's deadliest enemies, MCU Parker will also be without the support of some of his closest friends, both in and out of costume. For one, Uncle Ben is completely absent from Homecoming, as everybody involved agreed that story didn't need to be told onscreen a third time. But Feige's statements regarding the rogues' gallery also imply that Norman Osborn and his son Harry are on the shelf, along with mentor/nemesis Curt Connors/The Lizard—all important relationships to comic book Parker.

Other important friends and allies can never interact with MCU Parker due to rights issues, such as Reed Richards, Johnny Storm, Wolverine, and—perhaps saddest of all—Deadpool. Also, because of the current no-crossover policy, friend and regular partner Matt Murdock/Daredevil will remain segregated on Netflix along with Luke Cage and Iron Fist. And last but not least, Homecoming featured not one single mention of either Mary Jane Watson or Gwen Stacy—and Marvel's apparent aversion to repeating characters from the previous franchises suggests that they may be permanently benched as well.