The Most Confusing Plot Twists Explained

We go to the movies to be told a story — and for the most part, that generally means watching characters move through a clearly delineated beginning, middle, and ending, with pretty much all the plot threads sewn up by the time the end credits roll. That doesn't mean there aren't some delightful exceptions, however — in fact, some of the finest films in history have thrown audiences a confusing curve ball or two.

Leaving just enough open to interpretation can make a movie immortal, ensuring that fans will be left debating the meaning of their favorites for years to come. Modern mind-benders like Memento and Fight Club have been discussed in depth online for years, but we've assembled an extra assortment of movie twists from other challenging films that remain largely unexplored. Some are from recent years, others are classics that still hold secrets — and all of them are worthy of your closer examination. These are the most confusing plot twists, explained.

Lost Highway's identity swap

Arguably no living filmmaker is better known for mind-bending twists than David Lynch. Mulholland Drive is one of the defining works of his career, in part because its climactic shift into an alternate reality has left audiences thinking about its dream logic for years. But before Mulholland, Lynch opened another puzzle box of shifting identities that's even more twisted: Lost Highway.

In Lost Highway, we meet Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a jazz musician accused of murdering his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette). Fred goes to jail, but on their morning cell check, guards discover that Fred's place has been taken by Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a younger man who lives with his parents (Gary Busey and Lucy Butler) and works as a mechanic. Pete can't fully remember where he was before he woke up in jail, but he's soon entangled with Alice Wakefield (also Arquette), a woman who looks exactly like Renee Madison.

In typical Lynch fashion, no one shows up to explain the story, but the meaning is hiding in plain sight among seemingly mundane details. Things like Fred's distaste for home camcorders, characters Alice disappearing from a photograph, and multiple disappointing attempts at lovemaking all point to a frustrated sense of masculinity in denial. Film critic Jim Emerson points out at a passage in Lynch's book, Catching the Big Fish, which revealed that coverage of the O.J. Simpson trial influenced the story of Lost Highway, though even he didn't realize it at the time.

"I wondered how, if a person did these deeds, he could go on living," Lynch wrote. "And we found this great psychology term, psychogenic fugue, describing an event where the mind tricks itself to escape some horror." Fred Madison, then, is a man who murdered his wife and invented an entire alternate life story to escape his own guilt.

The Last Jedi's parental revelation

The Last Jedi just might go down in history as the most polarizing of all the Star Wars films. Many fans and critics were thrilled by writer/director Rian Johnson's deconstruction of the franchise's mythology. An equally vocal group, however, complained about many of the eighth episode's plot swerves. One of the most controversial revelations was the parentage of Rey (Daisy Ridley). After The Force Awakens introduced Rey with vague questions about the identity of her long-lost parents, The Last Jedi had her confront the truth: they were nobody.

While some saw this twist (or non-twist, as the case may be) as a copout, Johnson's reasons were carefully considered. Thematic parallels are an essential part of the Star Wars formula ("They rhyme," George Lucas likes to say), and Last Jedi could only ever live in the shadow of The Empire Strikes Back's "I am your father" reveal. "With that one line...suddenly, that easy answer gets taken away from you, and he's something that our protagonist has a relationship to," Johnson explained on an episode of Empire's film podcast. For Rey, on the other hand, "The hardest thing to hear is, 'Nope, this is not gonna define you.'"

Rey's arc in The Last Jedi is all about her looking for her place in the grand struggle between the First Order and the Resistance. She expects to find her destiny within the truth of her heritage, and why wouldn't she? Star Wars has always been about generational conflict. But, as foreshadowed by her vision of endless reflections stretching behind and ahead of her, Rey's is a story about defining one's own identity. Love the reveal or hate it, it's bold, carefully considered, and far from lazy.

Fargo's awkward acquaintance

Joel and Ethan Coen's comedy-thriller Fargo was an instant smash upon its release in 1996, earning accolades and box office receipts unlike anything the brothers' earlier work had achieved. Its screenplay even won an Academy Award, in recognition of its tight plotting and strikingly unique tone. But one thing that has always puzzled audiences, even some of the film's most ardent fans, is the significance of a particular character who is only present for a single scene: Marge Gunderson's old friend, Mike Yanagita.

In the midst of her investigation into the film's central kidnapping, Marge (Frances McDormand) accepts a lunch invitation from her high school acquaintance, Mike (Steve Park). He awkwardly fumbles through their conversation, telling her about his marriage to their classmate Linda. Linda, he reveals emotionally, recently died of leukemia, leaving Mike desperately lonely. Later, Marge relays the uncomfortable encounter to another friend over the phone, and learns that not only is Linda alive, but she was never married to Mike and in fact had to get a restraining order to protect herself from his obsessive stalking. Marge is visibly disturbed, but never mentions the situation again.

As documented by Vox, there are two popular theories about the Coens' intentions in this scene, and both can be true. First, Mike Yanagita does have more impact on the main kidnapping plot than appears on the surface. One of the film's primary themes is the way the "Minnesota Nice" pleasantries of the Midwestern characters masks the shame and fear that can drive a man to desperation. Marge only approaches Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy) for a second interrogation after the Yanagita episode, and though she never says as much, it's because her unwavering trust in the honesty of those around her has just been challenged.

The other interpretation, as espoused by Noah Hawley, creator of the spinoff Fargo TV series, has more to do with the overall tone struck by the Coens. Fargo opens with a title card claiming that the film is based on a true story that occurred in 1987. It isn't, but the specificity of that date, combined with apparent non-sequiturs like Mike Yanagita, primes the audience to be more willing to explore the space of an absurd story. As Hawley explains, "It's one of those details where you're like, 'Well, they wouldn't put it in the movie unless it really happened.'"

The twisted road of the Fast and the Furious

The Fast and Furious series doesn't have a reputation for being particularly intricate or cerebral. It certainly started simply enough, with a cast of street racers doing crimes for the greater good and getting very emotional about family. But as the franchise stretched on and branched out into ambitious new plot threads, it quickly revealed itself as a labyrinth of non-linear narrative that must be explored a quarter-mile at a time. Vox's handy guide to the franchise, complete with visual aids, breaks down the chronology.

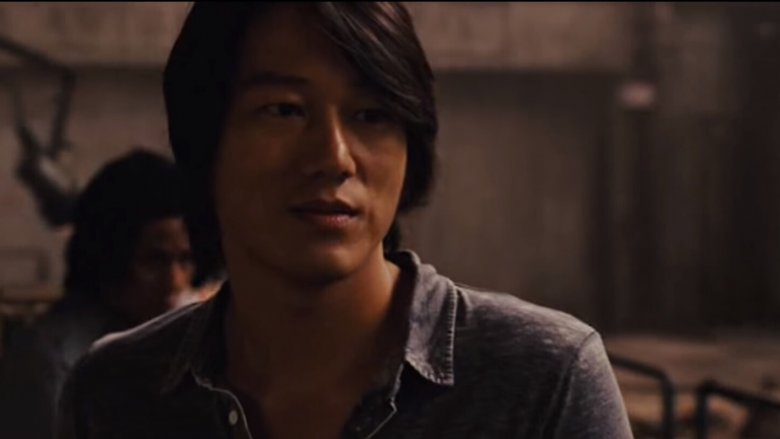

By the third film, 2006's Tokyo Drift, it appeared the series was going the anthology route, with a completely new cast of characters headed by Sean Boswell (Lucas Black), a juvenile delinquent sent to live with his father in Tokyo, where he's taken under the wing of Han (Sung Kang), a racer who teaches him the power of drifting. Han is tragically killed during a race, prompting Dominic Toretto (Vin Diesel, in a cameo) to appear and declare himself an old friend of Han's in the final scene.

Now here's where the twist comes in. 2009 saw the release of Fast & Furious (not to be confused with the first film, The Fast and the Furious), which reunited the original cast and Han. After the opening action sequence, there's a time jump as the crew goes their separate ways. Han says he's off to Tokyo, leading the audience to believe that the rest of the fourth film takes place concurrently with the third. But no, Han's back again in a more significant role in Fast Five, and sticks around through Fast & Furious 6 (note the ever-shifting nomenclature that makes the timeline even more complicated to discuss).

The story finally catches up to Han's death in a post-credits scene at the end of the sixth movie, which reveals that Deckard Shaw (Jason Statham), the villain of Furious Seven, was actually responsible for the "accident" in Tokyo Drift. Was this mystifying maze of life and death a brilliantly plotted master plan? Probably not, or it wouldn't be so obvious that Tokyo Drift takes place in 2006 rather than 2013, which you can tell by the cars, the cell phones, and the way Lucas Black ages a decade between shots in Furious Seven. At any rate, series writer Chris Morgan has recently speculated that Han could come back yet again, promising that the saga of our favorite fast family isn't about to get any less complex.

American Psycho's clean apartment

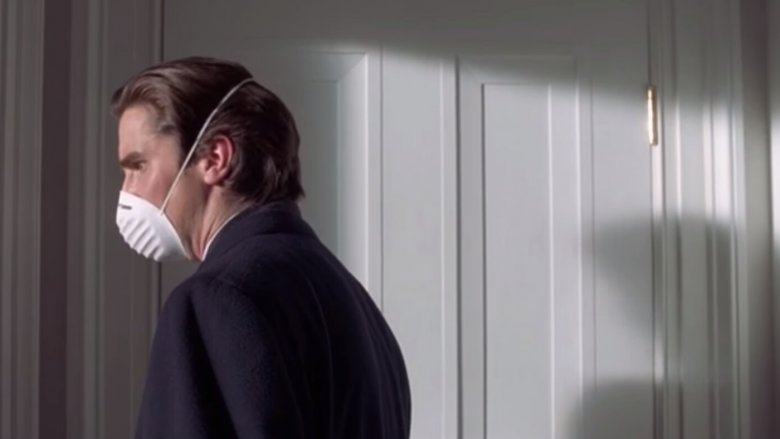

Director Mary Harron's adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis' novel American Psycho is designed to leave audiences wondering how much of what they've seen is "real." As the film reaches its climax in an over-the-top killing spree riddled with explosions and swooping police helicopters, it becomes impossible to deny that Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) isn't an entirely reliable narrator. But it's the next morning that brings the twist that casts a new light on the whole movie.

Bateman goes to the apartment he last left covered in blood and full of corpses, ready to clean up all evidence of the crimes he's been committing there for weeks. He's disturbed to find the place empty and freshly painted. A rental agent (Patricia Gage) confronts him, asking if he's there because he saw an ad in the Times. He says he did, but she reveals there was no such ad, and insists he should leave, which he does.

What does this scene represent for the plot? According to screenwriter Guinevere Turner, "He did do all this stuff and he still cannot stand out...he's stuck. He's practically begging, saying, 'I kill people! I'm not like all of you, I have something special about me!' And they're like, 'Wait, who are you?'" Specifically, the apartment has been cleaned and put back on the market because Bateman's crimes are so unremarkable in the film's viciously heightened universe of Wall Street capitalism that all attention, even punishment, will elude him forever.

The Shining's shifting Grady

There are a lot of lists on the internet cataloging mind-bending movie twists, and The Shining is on most of them. Usually, though, it's because of the final shot that reveals Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) present at a party 60 years before the events of the story. But there's an even more mystifying anomaly earlier in the film that goes largely overlooked: the two men named Grady.

When manager Stuart Ullman (Barry Nelson) explains the Overlook Hotel's history to Jack in the opening job interview scene, he reveals that a previous caretaker named Charles Grady murdered his family while suffering from "cabin fever." Much later, a ghostly servant (Phillip Stone) introduces himself to Jack as Delbert Grady, and Jack quickly identifies him as the man Ullman told him about. Grady all but confirms this as their conversation continues, with vague references to his need to "correct" his children.

So if this is indeed Jack's predecessor in his dual role of caretaker/murderer, why does he have a different first name in death than he did in life? The switch is not something that occurs in Stephen King's novel, but a character suddenly changing names is far too glaring to be a continuity error, especially for a filmmaker as detail-oriented as Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick never commented on the apparent discrepancy, but it's almost certainly tied into that final photo surprise.

The sprits of the Overlook are all about dehumanizing the people they want to use. This is obvious in Grady's use of racial slurs, the encouragement of Jack to oppress his wife, and even the scorn shown to Jack when he fails to murder her. We can assume that Grady's journey from mortal blue-collar worker to ghostly middle manager is much the same as what the hotel has in store for Jack. Perhaps this case of confused identity, then, is another weapon in the Overlook's arsenal of subjugation. When you sell your soul to its ruling class, you're stripped of your will, your morality, and even your name, until you truly believe you've always been there.

A Nightmare on Elm Street's twisted awakening

Wes Craven's original A Nightmare on Elm Street launched a franchise that would span three decades, six sequels, a remake, a TV show, and a showdown between horror icons. But Craven never envisioned the series living beyond one film, and intended to wrap up the saga of Freddy Krueger at the end of the first story. Executive producer Robert Shaye disagreed, hoping to leave the door open for a follow-up, and the compromise they reached resulted in a fairly baffling finale.

As recounted by Craven and Shaye in Vulture's Oral History of A Nightmare on Elm Street, the original ending was to find Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) fully triumphant over Krueger (Robert Englund), with all of his horrors reversed as she drives off into the sunset with her friends. To appease Shaye, Craven shot multiple variations on the final scene that hinted at a lingering evil. The final cut has the convertible carrying Nancy and her friends reveal a roof bearing Krueger's trademark red and green stripes, just as her mother (Ronee Blakley) is pulled through a window by his razor glove.

What does it all mean? When Nancy reappears in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, she mentions that Krueger killed her friends and her mother. We can assume, then, that Nancy undoing the murders in her defeat of Krueger was a dream in itself. In the documentary Never Sleep Again, Englund proposes that the entire film is "a precognitive nightmare," and that the final scene represents the story beginning to come true. The most definitive answer may be that there is no literal interpretation of the ending, beyond a use of dream logic to promise that the nightmare will never truly end.

Rocky Horror's aliens and Nazis

If you've only seen The Rocky Horror Picture Show at midnight screenings, with people yelling at the screen and dancing in the aisles, you may not even realize it has a plot. It does, and it's pretty wild. In the midst of all the outlandish glam musical numbers and sexual escapades, there's a story about aliens and Nazis unfolding near its halfway point.

After Dr. Scott (Jonathan Adams) arrives just in time for an awkward dinner scene, Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry) correctly guesses that Scott investigates UFOs for the United States government. Frank also accuses Scott of secretly being Dr. Von Scott, an assertion that makes his old pupil Brad (Barry Bostwick) visibly upset. The conversation is dropped, leaving an unresolved plot point that requires a certain amount of historical context to understand.

Frank is referring to German scientists who accepted work with the allied countries after the end of World War II through initiatives like Operation Paperclip. Many Germans in America at this time changed their last names to avoid the stigma of Nazism. Frank is intimating that Dr. Scott is not only German (a hilarious "secret" given his over-the-top accent), but a former Nazi. This gives ominous extra context to his later insistence that "society must be protected."

Vertigo's lookalikes

40 years before David Lynch confounded audiences with Lost Highway's pair of lookalike characters played by the same actress, Alfred Hitchcock pulled a similar trick in Vertigo, albeit in service of a very different story. Hitchcock introduces us to Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart), a private investigator who has retired from police work due to his struggles with the titular disorder. His old friend Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) hires Scottie to trail his wife, Madeline (Kim Novak), because he fears she's possessed by the spirit of her great-grandmother, who committed suicide.

Scottie saves Madeline from an apparent attempt to drown herself, and the two quickly begin to fall in love. But Madeline is drawn to the mission where her great-grandmother, died, and rushes up the bell tower. Scottie's vertigo prevents him from following, and he watches in horror as she falls to her death. He's so shaken that he's committed to an institution — and upon release, he meets a woman named Judy (Novak again), who looks eerily like Madeline. They begin an intensely unhealthy affair in which Scottie becomes obsessed with making Judy into a perfect recreation of the woman he lost.

A flashback reveals the twist that Scottie never learns about: that the "Madeline" Scottie knew was always Judy, who Elster hired in an elaborate plot to murder his wife. All of the supernatural elements of the story were concocted to confuse Scottie, whose vertigo was guaranteed to leave him a helpless witness to the fake suicide. As for what it all means, the most common interpretation is that Vertigo is all about the male gaze, though critiques like Laura Mulvey's "Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema" and The Artifice's "Motional Control or Compromise?" have debated whether Hitchcock succeeded in making a worthwhile point on the subject.

Fire Walk With Me's dream message

Returning again to the many twists in David Lynch's work, we find one that very recently became more relevant than expected. Fire Walk With Me served as Lynch's 1992 follow-up to the original two seasons of Twin Peaks, exploring the last days of Laura Palmer's life. This naturally makes the film a prequel — but in a very Lynchian twist, it's also a sequel.

In the middle of the film, Laura (Sheryl Lee) has a dream in which she explores the rooms inside a painting on her wall (it's Twin Peaks, so things like that happen). When she (seemingly) awakens, she finds Annie Blackburn (Heather Graham) next to her. Laura doesn't know Annie, but the audience will recognize her from the finale of the show's second season. Annie instructs Laura to write in her diary that "the good Dale is trapped in the Lodge and can't leave." None of this means anything to Laura, who will be dead before Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) ever comes to town, and the film never references it again.

The payoff for this strange interlude plays out in silence during the film's very last scene, in which the just-murdered Laura finds herself in the Red Room with Dale, and they share a knowing and comforting look. It's essential to the happy ending Lynch has in store for Laura that she has, in fact, always known Dale, thanks to the nonlinear dream logic of how time works in the Black Lodge. She just can't understand fully until she arrives in the afterlife. Those diary pages, incidentally, became a key plot point in the third season of Twin Peaks, a full 25 years later.