That's What's Up: Do We Really Need The Fantastic Four?

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Do we still need the Fantastic Four? — @_Miller_Andrew

Of course we do. Who else is going to deal with Galactus when he shows up and tries to eat the planet?

Okay, all joking aside for the next sentence or so: The Fantastic Four are in a pretty weird position. They're not just one of Marvel's major franchises, they were the foundation of Marvel Comics as we know it, and arguably the foundation of all modern superhero comics besides. With 108 issues by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Fantastic Four was the book by the creative team at Marvel, and sits at the core of everything those first ten years were built on. These days, though, not so much.

Despite the fact that there has been at least one genuinely great FF run in every decade since the book began — and usually two or three — the Marvel Universe as it stands right now seems to have largely moved past the team, and is doing just fine without them. We're actually at the point where the surprising thing isn't that you asked the question of whether we still need them, but that I actually have to stop and think about the answer.

Marvel's First Family

Here's the thing about Fantastic Four: when I say it was the book that basically invented modern comics, I'm not exaggerating. If anything, I might actually be understating it. Those first few years from Lee and Kirby are arguably more influential than any other superhero comics, with the possible exception of Superman's debut in Action Comics #1 — and even then, that's only because it's the book that literally invented the genre. FF, on the other hand, not only redefined it, but provided the blueprint and foundation for everything that came after.

In retrospect, it was — and this is one of those few times when I can actually use a phrase that's usually reserved for supervillains — elegant in its simplicity. It took those core ideas that had been making superhero comics work for 20 years — the powers, the cool codenames, the costumes, the over-the-top enemies — and combined them with everything else that had been going on in comics.

It's an approach that has a lot ot do with the history of the long-standing rivalry between DC and Marvel. There was a massive explosion of new superheroes in the early '40s after Superman kicked off the genre, but when you got right down to it, National, the company that would become DC Comics, had Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, and that was pretty much all that mattered. Sure, there were plenty of great and interesting characters — like the original Black Widow, who was essentially Satan's personal assassin, or Nightmare and Sleepy, a professional wrestler who traveled from town to town grappling by day and fighting weird supernatural threats by night — but none of them occupied the same level of pop culture success that you saw from DC's big three. The only one who did was Captain Marvel, better known today as Shazam, whose adventures outsold Superman's at the height of his popularity, but thanks to a lawsuit, that didn't last. By the time the Comics Code rolled around in the mid-'50s to put a stake in the heart of horror and crime comics, they'd pretty much cornered the market on superheroes.

The superhero soap opera

That left other publishers to toil in different types of comics. The big one, of course, came from stuff like the Disney comics, where Carl Barks was telling massively influential adventure stories and creating characters like Scrooge McDuck, but there were other genres floating around, too. Monster comics, pulpy sci-fi, romance, westerns. Those were the kinds of books that Atlas, the company that would become Marvel, was putting out in 1960 — and those were the kinds of stories that they mashed up with superheroes in the pages of Fanatstic Four.

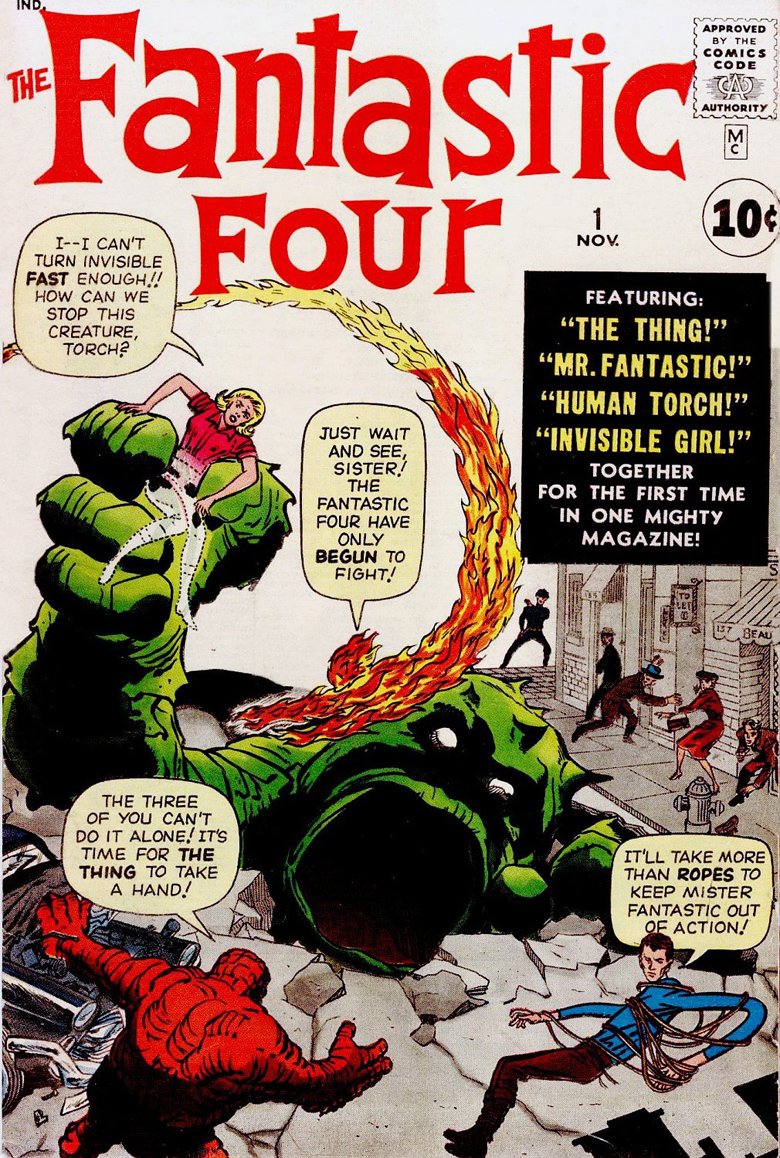

You can see it all on that first cover. They're clearly superheroes — there's a dude flying around on fire, a callback to the original Golden Age Human Torch that might spark some memories in older readers — but they're also fighting the same kind of giant monster that would've been seen in "horror" books like Tales of Suspense. Some of 'em don't even have costumes, which is a pretty radical departure from the capes, cowls, and All Bat Everything that you'd see over at the Distinguished Competition. They don't even have secret identities! How could they? One of 'em's a friggin' orange rock monster!

That first cover also pulls one of the greatest marketing tricks in the history of comics: announcing that the FF are finally "together for the first time" in their first appearance ever. It's such a good bit that you never really bother asking just who the hell was supposed to have tied Reed Richards up, which is good. If you think about it too hard, you'll inevitably come to the conclusion that Giganto up there definitely interrupted Reed and Sue's weirdly public experimentation with BDSM.

Galactus invents modern comics

Either way, that was the big secret of the early years of Fantastic Four: they were superhero comics with the structure of sci-fi and monster stories. They fought their share of supervillains, of course — Dr. Doom, maybe the greatest supervillain of all time, made his debut in #5 — but they spent a lot of their time dealing with pulpy sci-fi threats and squabbling in an ongoing soap opera that stood in a stark contrast to other superheroes of the early '60s. Then, in 1966, Galactus came along and changed everything forever.

Again, that's not an exaggeration. If you've never gone back to FF #48, 49 and 50 and read the original Galactus trilogy, you'd likely be shocked at how much it feels like a modern event comic. It's spread out over three issues at a time when most Superman stories were still eight pages, with stakes that just keep increasing in the face of a cosmic threat that's going to wipe out an entire planet, introducing concepts that are quite literally beyond the understanding of the heroes and asking them to win anyway. And on top of all that, the wildest thing about it might be that it all wraps up in the middle of #50 so the story can move on to Johnny Storm's first day at college. That's how much the soap opera was blended in there — it shared space on the page with Galactus, the Devourer of Worlds.

If you have read those issues, this is old news, but there is an actual point to this history lesson: the Fantastic Four were the core of the universe. This was the book where cosmic heroics blended with down-to-Earth, relatable concerns, where characters like the Inhumans, the Hulk, Black Panther, and Daredevil were either introduced or given a showcase, stitching together a cohesive universe.

It was the book at Marvel. Until it wasn't.

Fading focus

The Fantastic Four gave the Marvel Universe the blueprint and the foundation that it could build on, but here's the problem with blueprints: they're not buildings.

In the same way that Captain Marvel came along in 1939 and improved on the initial idea of Superman — to the point that Cap's primary writer, Otto Binder, would be hired by DC and go on to become the definitive Superman writer of the Silver Age — everything Marvel did after the FF is easy to read as an improvement on those same ideas, often just combining them in new ways. Johnny Storm's version of being a super-powered teenager and the Thing's reluctant, tragic heroics were synthesized into Spider-Man. Mr. Fantastic's genius was mixed up with the Thing's monstrous form for the Hulk. The team's interpersonal bickering paved the way for the X-Men. The modern version of Tony Stark, the super-genius who's always thinking too fast for anyone else in the room — and for his own good? That's just Reed Richards with baggage. The only thing they couldn't really improve on with a new iteration was Dr. Doom, but that was fine — he wound up having some of his most memorable stories as a foil for characters like Iron Man and Dr. Strange anyway.

The FF stayed relevant and interesting for decades, but once Kirby was gone to invent a whole new mythology at DC, the team lost a little bit of its luster, and was quickly supplanted as the core of Marvel Comics by all those other characters standing on the foundation they'd started laying down in 1961.

It actually led to a weird little quirk of Marvel Comics as a company. Rather than dividing its history up into defined ages based around events, like you can with DC, it's actually easier to break down Marvel's eras by identifying which characters the company was built around. Spider-Man has pretty much been a constant since he was introduced, but when you look at the big franchises that sit at the core of the universe, it's easy to see how it breaks down. In the '60s, it's unquestionably the FF for the entire decade. In the '70s, though, it becomes the X-Men, and stays that way for a real long time, until the Avengers finally show up to take their place at the top. Seriously: as hard as it might be to believe when you're looking back at it from a time when they're the biggest thing in comics and blockbuster movies, the Avengers were never really a big deal until the mid-2000s.

Your favorite team's favorite team

The thing that kept the FF relevant for so long was this idea that they were just in a completely different class than anyone else in the Marvel Universe. They'd been at it longer, they handled bigger threats, and they had concerns that went well beyond other heroes' struggles with secret identities and making sure Aunt May could get her prescriptions. The Avengers had some great characters, but they weren't the team you were going to call when Galactus showed up or if you needed to dive into the time stream, you know? Captain America might save the world, but the FF were out here saving the multiverse.

There's actually a great story about that same idea. It happens in Fantastic Four #334, during Marvel's greatest crossover, Acts of Vengeance. The basic idea is that due to some shenanigans from Loki, all of Marvel's villains decided to switch opponents to see if they'd have better luck dealing with each others' arch-nemeses. It led to some great, bizarre match-ups, like the Punisher fighting Dr. Doom, Ultron taking on Daredevil, and that great issue where Magneto shows up in the middle of an issue of Captain America to drop Red Skull into a hole in the ground to die slowly for being a Nazi.

The Fantastic Four, on the other hand, got to deal with a bunch of B-list Spider-Man villains like the Beetle and the Shocker, and wound up dispatching them pretty effortlessly. They even clown on the very idea that these guys could provide a threat on the covers, and it makes perfect sense. The FF dealt with a giant purple space god coming down to eat the planet, are Plant Man and some dude with pocupine powers really going to provide a threat?

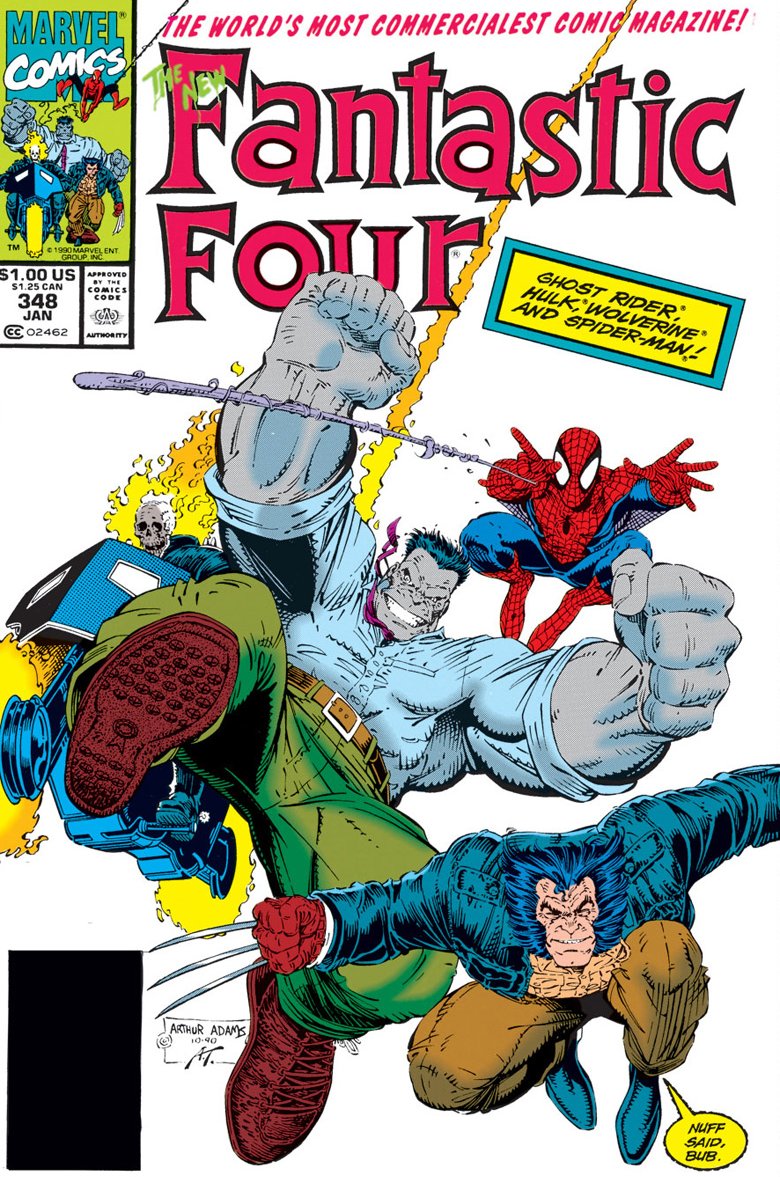

It's worth noting, by the way, that this issue comes in the same run by the legendary Walt Simonson that also includes the tongue-in-cheek introduction of the "New Fantastic Four." It's a great bit of commentary on changing tastes, slapping together a very commercially viable team of Spider-Man, Hulk, Ghost Rider and Wolverine for a mission to rescue the real FF. Even then, in 1990, Simonson and artist Art Adams were asking if the FF were still relevant.

Clobberin' Time

Their answer then was, of course, yes. The FF deal with things that other Marvel characters just don't, and that weird family sci-fi adventure aspect gives them a place in the universe.

That said, 1990 was a long time ago, and things have certainly changed quite a bit since then. It's easier to draw that big dividing line between the FF and the rest of the universe, but it's a lot harder when there are so many other groups all vying for the same sort of adventure. Just look at the modern idea of the Avengers, the folks you see running around in the movies. How do you justify the need for the FF when you've got a team that has a troubled genius in Tony Stark, the monstrous pathos of the Hulk, the raw power of Thor, and the moral center of Captain America, especially when they're dealing with cosmic threats from Thanos and the Infinity Stones? They even have Spider-Man hanging around, and he's literally just the better, more interesting version of the Human Torch! If that's who's filling the role that would normally go to the FF, then what do we get by having them around beyond just the acknowledgement of historical significance?

The only character that's instantly and easily identifiable as relevant is the Thing, because he's the purest, most concentrated capital-M, capital-C Marvel Comics character of all time. He's the prototype that still works. That's one of the reasons that Marvel's two long-lasting team-up books, Marvel Team-Up and Marvel Two-In-One, starred Spider-Man and the Thing, respectively. They're the purest forms of what it means to be a Marvel hero, which is why you can slide them into an adventure with everyone.

All Doom and gloom

All of which leads us back to the big question: do we actually need these characters? But having thought about it, I think there's a better question to ask that deals with the same idea: do we actually want more Fantastic Four stories?

There are other groups that do what the FF does, and with the exception of Ben, there are other characters that do what they do better. But because they were first, because they were the trailblazing team that held the Marvel Universe together, nobody else does what they do the way they do it. No other team is put together quite this way, and while historical significance isn't always a guarantee that something's actually worth reading — just try to dig into 90 percent of Golden Age comics — there's a history there that can provide its own foundation for the future, too.

Tony Stark isn't going to react to a scientific mystery the way Reed Richards is. Thor isn't going to deal with an unstoppable enemy the way that Sue Storm is. Even Spider-Man doesn't have the stupidity and blowhard confidence that allow Johnny to twist a story into something new. Dr. Doom is a great villain for literally any hero who wants to step up for a fistfight, but he's never going to have a connection to someone that matches his all-consuming hatred for Reed Richards.

The question, then, is whether or not we want those stories, and I do. Looking back over the team to try to figure this out, I'm struck by just how good those comics actually are, and while the team has fallen out of favor for now, the only thing they need to turn it all around is one more grand adventure.

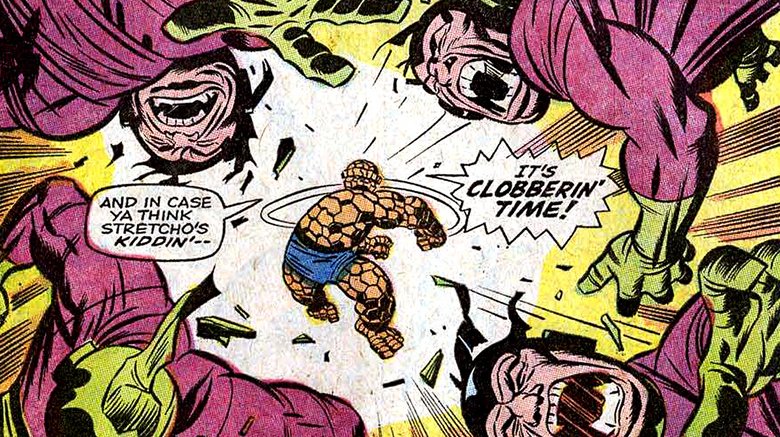

And it's always clobberin' time somewhere.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."